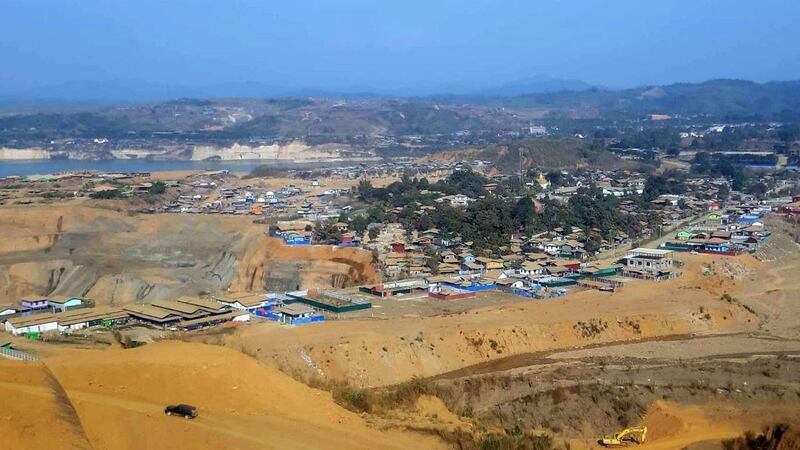

Illegal gold mining has increased ten-fold in Myanmar’s Kachin state since the military seized power in a coup more than two years ago, a new report and sources said, amid a decrease in federal oversight in the region.

Illegal mining of gold, as well as jade and rare earth minerals, is rampant in Kachin state, where successive governments have failed to regulate the industry for generations. However, the number of unsanctioned operations has ballooned since the military’s Feb. 1, 2021, takeover amid conflict between junta troops and armed resistance forces in the region.

The number of gold mining rigs on the Ayarwaddy River in Kachin’s Myitkyina township jumped to more than 1,000 in 2021 and more than 800 in 2022 from just over 70 in 2020, according to a report released Sunday by the Kachin State Accountability Resource Governance group, or K-SAG, which began monitoring the use of resources in the state prior to the coup.

“There weren’t many, but some arrests and inspections took place [mainly] in Puta-O township before the coup,” K-SAG’s head of research, who gave her name as Alice, told RFA Burmese.

However, in the 26 months since, authorities have yet to carry out an inspection or make an arrest in connection with illegal mining in Kachin, allowing the problem to proliferate in the region, she said.

“Now that illegal gold mining has increased more than 10 times, the situation is very bad here,” Alice said. “The businesspeople who started illegal mining in 2021 as a test to the legal system under the new military regime are now digging freely and greedily. The situation got worse in 2022 and we are sympathetic to the voices of the local residents.”

Without measures in place to combat the problem, it will only become worse in 2023, she said.

Surge in resource exploitation

The report, which was published based on surveys and interviews with 330 residents from nine townships in Kachin between June and November last year, found that the exploitation of natural resources – including rare earth minerals, amber, gold and timber – had increased overall in the state since the coup.

“Areas of Hpakant [township] were already damaged [by mining] even before the military coup, but since then, all remaining areas have also been damaged,” the report said. “Both private and large-scale mines were operating there before the coup, but in accordance with government guidelines. These days, they operate without following any regulations or guidelines, which is the reason for the destruction.”

Despite the overall increase in resource exploitation in Kachin, gold mining had seen the largest increase since the takeover, K-SAG said, noting that such operations are approved and taxed by the Kachin Independence Army, the military regime, and local anti-junta paramilitary groups – depending on which faction controls the territory.

According to K-SAG, entrepreneurs setting up a one-acre gold mining operation can expect to pay fees of 5 million kyats (U.S.$2,380) each to the KIA and local paramilitary groups and 4 million kyats (U.S.$1,900) to the junta each season, in addition to fees for machinery.

By comparison, entrepreneurs who acquire a 100-square-foot plot for mining jade in the Kachin township of Hpakant must pay 150-200 million kyats (U.S.$71,400-95,200) to the KIA and 200-300 million kyats (U.S.$95,200-142,800) to the junta, the report said.

According to the Kachin State Mining Department, authorities collected more than 500 million kyats (U.S.$238,000) in taxes in 2020. However, while the number of mining operations in Kachin has skyrocketed, authorities collected only 238 million kyats (U.S.$113,300) in 2021 and 325 million kyats (U.S.$154,700) in 2022, the report noted.

Loose regulations

Win Ye Tun, the junta’s social affairs minister and spokesman for Kachin state, confirmed to RFA that no official mining rights had been granted since the military takeover.

“The government has not officially permitted any mining rights for natural resources such as jade and raw earth minerals,” he said.

But he rejected K-SAG’s claim that the junta had failed to police the industry in Kachin.

“Since the number of illegal mining operations has increased, the government is continuously making arrests and taking legal action [against violators],” he said.

Residents and environmental activists told RFA that mining companies pay bribes to both the junta and the rebel Kachin Independence Organization to look the other way as they operate illegally.

Col. Naw Bu, the information officer for the KIO’s armed wing, the Kachin Independence Army, also took issue with K-SAG’s findings, telling RFA that resource mining in Kachin state is being done “in accordance with regulations” set by the Kachin Independence Organization political group.

“They prohibit mining in populated areas, on civilian farms and at historical sites,” he said. “The KIC [Kachin Independence Council] has laid down guidelines. Local administrations have to decide whether or not to issue mining permits in accordance with those guidelines.”

Chinese entrepreneurs

K-SAG’s report also found that the gold mining industry in Kachin state, which borders southwestern China’s Yunnan province, has become increasingly driven by Chinese entrepreneurs since the coup. It said some 19% of gold mining in the region is now controlled by Chinese interests.

A resident of Chipwi township, one of five townships in Kachin – along with Shwegu, Myitkyina, Wingmaw and Tanai – with the highest concentration of Chinese-led mining operations, told RFA that gold mining is virtually unchecked in the region.

“The mines are digging in the areas too close to the town along the May Kha River – something that had never been done before,” he said, speaking on condition of anonymity due to security concerns. “The number of illegal mining operations has exploded since the military coup.”

The resident said that entrepreneurs and experts at the gold mines in the area “are Chinese nationals,” adding that rare earth mining had also increased in Chipwi since the takeover.

According to statistics released by China’s Customs Department in January 2023, the value of rare earth minerals exported from Myanmar to China increased to more than U.S.$800 million in 2021 from only U.S.$387 million a year earlier, before decreasing to more than U.S.$600 million in 2022.

K-SAG researcher Alice told RFA that resource exploitation in Kachin is in “urgent need of regulation” by whichever party is receiving money to approve it, in order to halt environmental degradation in the region.

“The [junta] and all other stakeholders are responsible, in my opinion,” she said. “People here wish to protect the environment but they are not in the position to do so and even the areas that had previously benefited from regulation are now at risk.”

Translated by Myo Min Aung. Edited by Joshua Lipes and Malcolm Foster.