Myanmar’s ethnic minority insurgent groups are grappling with a growing problem as they take over larger areas from junta forces in a surge of fighting since a 2021 coup: how to maintain law and order with few resources and while under constant threat of attack.

The Karen National Union, or KNU, controlling areas of Kayin state, is among the groups dealing with rising violent crime rates, especially offenses against minors, while struggling to maintain governance amid battles with junta forces.

“When there is conflict, there is not a normal situation. Whoever commits crimes like this, they have a lot of chances to flee,” said KNU spokesperson Saw Taw Nee, highlighting the difficulties in prosecuting offenders amid the chaos of war.

The conflict has displaced more than 229,000 people in Kayin state alone, according to the U.N. and amidst the turmoil, the KNU’s justice system has been pushed to its limits, resulting in controversial measures to combat heinous crimes.

Saw Taw Nee confirmed that “two or three” death sentences had been carried out in recent years, but declined to comment further, citing a lack of knowledge on the details. The KNU’s Department of Judiciary did not respond to requests for comment from Radio Free Asia.

In January 2024, a 60-year-old man was sentenced to death for raping two 12-year-old girls. This followed a 2022 case where two men received death sentences for the rape and murder of sisters aged 9 and 12.

These cases underscore the KNU’s resort to capital punishment, despite criticism from human rights organizations.

“As a human rights organization, we utterly condemn capital punishment in all circumstances,” said Saw Nanda Hsue of the Karen Human Rights Group. However, he acknowledged the complex reality in the “absence of proper mechanisms to hold civilian perpetrators accountable.”

The challenges faced by the KNU are not unique. Other political organizations opposing military rule and trying to administer civilian populations, such as the United League of Arakan and the Karenni Interim Executive Council, struggle with similar issues.

A source asking to be cited as an observer of the Arakan Army insurgent force, part of the United League of Arakan political group, told RFA that the group did not have enough lawyers or judges, and “very inadequate” infrastructure and facilities while prisons are at a constant risk of being attacked by junta troops.

“As [they gain] more controlled area and more population, the ULA will definitely face an increase in all types of cases,” the source said in a statement. “In some areas, gender-based violence and sexual assault cases might be more heard [in the] public domain.”

He told RFA he was not aware of any recent executions under the United League of Arakan.

Huge caseload

Similarly, the Karenni Interim Executive Council in Kayah state has begun training police forces to handle an increase in looting of homes abandoned because of the conflict, and petty crimes, as well as security for civilians, said John Quinley, director of Fortify Rights. Quinley interviewed members of the police force, who told him about the shortage of both facilities and personnel.

“They said, ‘you know, it’s really difficult. We have airstrikes and artillery fire in this area almost on a daily basis. But we’re also trying to get these guys that are trying to steal goods from houses,’” he said.

“Even the amount of judges that you have is fairly limited and their caseloads are really high, and so you just have a lot of petty crime, you have also other cases that are related to prisoners of war or related to crimes that maybe the resistance forces committed that need to go through the courts, so it’s just really quite a big caseload.”

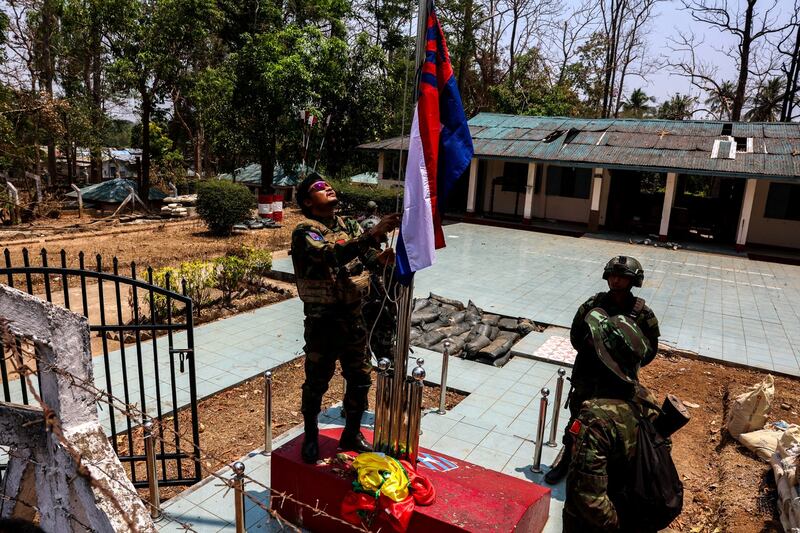

Ethnic minority political groups and their armies are increasingly taking over areas that have been devastated by the battles in which control over them was won.

“If you’re dealing with towns and villages that have been bombed out ... the courthouse is gone, the jails are gone, what they use for detention, and then once the sentences have been issued, prisons just simply aren’t available,” said Jonathan Liljeblad, an associate professor at Australian National University’s College of Law.

The United League of Arakan’s handling of more than 4,000 cases in recent years may soon be dwarfed by the growing caseloads across all areas controlled by ethnic minority organizations potentially leading to a bigger crisis in their makeshift justice systems.

“There’s a lot of challenges, like how to maintain the rule of law in our territory, especially prisons and the capacity of our people,” said the KNU’s Saw Taw Nee.

“We are still in a struggling time for our rights and liberties, so we could not focus on the specific issues like that,” he said in reference to the death penalty.

Edited by Taejun Kang.