Eighty representatives in Myanmar’s lower house of parliament have registered to discuss controversial proposed amendments to the country’s public assembly law, which rights groups oppose for their ambiguous language and additional restrictions on peaceful demonstrations in the emerging democracy.

The Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law, which was enacted in 2010 and took effect the following year under a military-backed government, allows public demonstrations only if organizers first obtain permission from local authorities, though it does not specify a time period. Those who violate the law are subject to three to six months in prison and a 30,000-kyat (U.S. $22) fine.

The proposed changes include clauses mandating jail terms for those who encourage others to participate in protests that could endanger Myanmar’s “security” and “public morality,” a requirement that protest organizers inform local authorities 48 hours in advance of a demonstration, and a stipulation that organizers provide funding details and identify the individual or organization financing their activities.

The amendments also allow police to break up a protest if they believe it violates laws on national security, rule of law, public order, or public morality, and establish a three-month jail term and an unlimited fine for those who provide financial or other support to demonstrators.

Another proposed amendment waives the 15-day time period during which police can bring charges against offenders under the law.

The amendments, put forth by the opposition Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), were passed by the upper house of parliament on March 7, despite 21 lawmakers from the ruling National League for Democracy (NLD) voting with some parliamentarians from the military and other parties against the changes.

Eighty of the lower house’s 440 lawmakers, including 60 military members of parliament, have registered to discuss the amendments — the largest number of army officers ever who have signed up to debate an issue, said Tin Htway, a legislator who represents Waw township in south-central Myanmar’s Bago region.

Lawmakers from the NLD, USDP, and ethnic Rakhine parties will also discuss the proposed changes, he said.

But under lower house rules, lawmakers who register to debate a bill are not automatically guaranteed participation.

The amendments come at a time when rights groups have accused the Myanmar government of backpedaling on freedom of expression and peaceful protest by using the law to jail activists.

Nevertheless, some NLD politicians and MPs say the changes are necessary to stop people from trying to undermine the government by funding protests.

“We understand people have freedom of expression under the democratic government, but we don’t think it is a good idea to attack and confront government for everything,” said NLD spokesman Monywa Aung Shin.

“What I think is that the NLD government is considering approving this bill to control this situation,” he said. “Although democracy allows freedom of expression, freedom should be attached to responsibility and accountability. There is a thin line between ‘democracy’ and ‘anarchy.’”

USDP pushes back

The USDP criticized the ruling party’s handling of the proposed legislation on Thursday during a press conference at its headquarters in the capital Naypyidaw.

USDP spokesman Nandar Hla Myint said parliament should approve proposals based on whatever is in the best interest of the Myanmar people and not take a partisan approach to them.

“The USDP submitted many good proposals last year that were in the interest of the people; some were rejected, some were just noted, and some were not discussed until the parliamentary session was about to end. Frankly, this deviates from the standard political norm.”

The NLD won a landslide victory against the USDP in November 2015 elections that brought to power the current civilian government of State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi and President Htin Kyaw.

Piake Htway, a member of the USDP’s central executive committee, said the NLD government should focus on resolving more pressing issues affecting the nation.

“We have many problems in our country, such as the Rakhine issue, poverty, increasing crime, international pressure, and a lack of rule of law,” he said, in a reference to an outbreak of violence in western Myanmar's Rakhine state that forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims to flee to Bangladesh.

“Twenty-nine political parties have requested that President Htin Kyaw meet with us because we would like to discuss these problems with him, but we haven’t had any response yet,” he said.

APHR weighs in

Several civil society organizations and NLD parliamentarians oppose the amendments to the law, arguing that they are too restrictive and were pursued without significant public consultation.

In recent years, rights groups have called for changes that would better protect rights to peaceful assembly and free expression and eliminate criminal penalties and vague restrictions on speech contrary to international standards.

On Monday, Jakarta, Indonesia-based ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR) urged the lower house of Myanmar's parliament to reject the current proposed revisions to the peaceful assembly law.

The group of lawmakers from across Southeast Asia said the proposed changes would place additional burdensome restrictions on the right to free assembly and expression as Myanmar transitions to democracy.

“If passed, the amendments would not only stifle freedom of expression and peaceful assembly, but would also mark a significant shrinking of democratic space in Myanmar,” said Philippine Congressman Teddy Baguilat, an APHR board member.

“It’s especially sad to see such moves made under Myanmar’s first democratically elected government in decades,” he said. “We had hoped to see a widening of space for civic freedoms, but instead the country appears to be backsliding.”

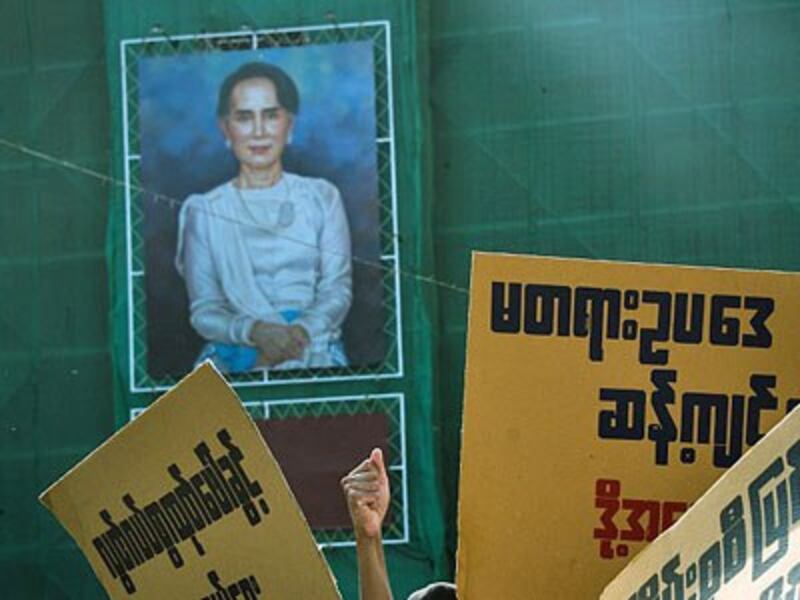

About 500 farmers, workers, and political activists marched in Yangon on March 5 to oppose the proposed amendments, arguing that they will limit free speech in the emerging democracy.

During the same time, nearly 200 Myanmar civil society organizations signed a petition against the proposed changes.

“Instead of strengthening the legal framework, these proposed changes simply make a bad law worse,” Baguilat said. “Many are ambiguously defined and significantly widen opportunities for the authorities to further criminalize peaceful protesters under a law, which had already been used numerous times against students, farmers, and journalists.”

Myanmar's parliament passed other amendments to the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law in 2014 and 2016.

Reported by Win Ko Ko Latt, Khin Khin Ei, and Htet Arkar for RFA’s Myanmar Service. Translated by Khet Mar. Written in English by Roseanne Gerin.