China’s outsourcing of rare earth mining to Myanmar has prompted a rapid expansion of the industry there, fuelling human rights abuses, damaging the environment and propping up pro-juna militias, according to a new report published Tuesday by rights group Global Witness.

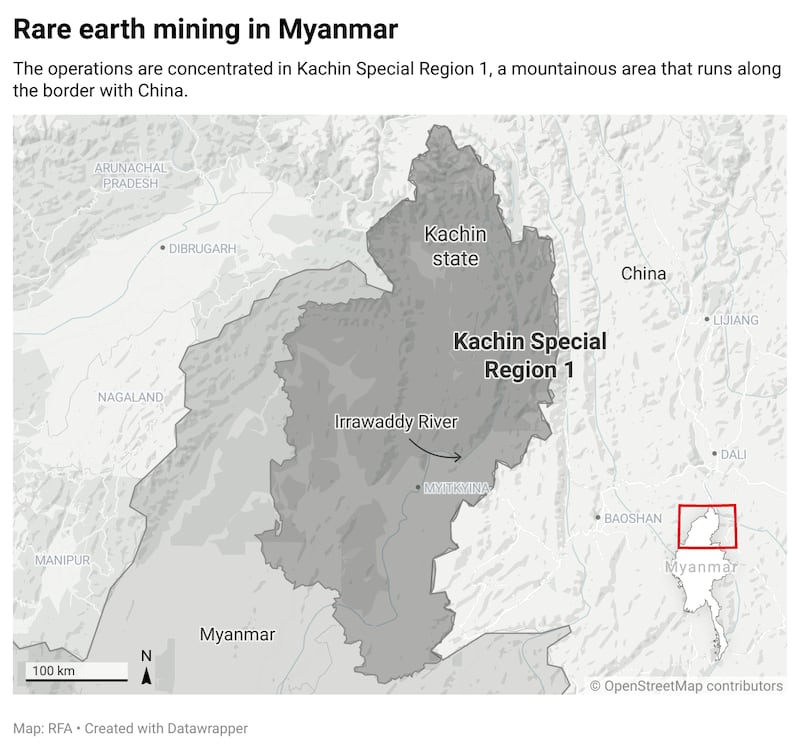

The report, entitled “Myanmar’s Poisoned Mountains,” used satellite imagery to determine that what amounted to a “handful” of rare earth mines in Myanmar’s Kachin state in 2016 had ballooned to more than 2,700 mining collection pools at almost 300 separate locations, covering an area the size of Singapore, by March 2022 — slightly more than a year after the military seized power in a coup.

Global Witness found that China had outsourced much of its industry across the border to a remote corner of Kachin state, which it said is now the world’s largest source of the minerals used in green energy technologies, smartphones and home electronics.

“Our investigation reveals that China has effectively offshored this toxic industry to Myanmar over the past few years, with terrible consequences for local communities and the environment,” Global Witness CEO Mike Davis said in a statement accompanying the release of the report.

The local warlord in charge of the mining territory, Zakhung Ting Ying, has become the “central broker” of Myanmar’s rare earth industry, the report said, along with other leaders of militias loyal to the military regime, making backroom deals with Chinese companies that are illegal under the country’s laws.

It said that his militia’s links to the junta mean “there is a high risk” that revenues from rare earth mining are being used to fund the military’s human rights abuses and crushing of dissent. Rights groups say security forces have killed at least 2,167 civilians and arrested more than 15,000 others since the Feb. 1, 2021, coup, mostly during peaceful anti-junta protests.

“Rare earth mining is the latest natural resource heist by Myanmar’s military, which has funded itself for decades by looting the country’s rich natural resources, including the multi-billion-dollar jade, gemstone and timber industries,” Davis said.

“Since the 2021 coup, the regime has relied on natural resources to sustain its illegal power grab and with demand for rare earths booming, the military will no doubt be spotting an opportunity to fill its coffers and fund its abuses,” he added.

Global Witness noted that the processes used to extract heavy rare earth minerals have polluted local ecosystems, destroyed livelihoods and poisoned drinking water. It said multiple health issues reported near the rare earth mines in China have also been reported by residents living close to the mines in Myanmar.

Meanwhile, civil society groups and community members — including indigenous people — who speak out against the illegal industry or refuse to give up their land to make way for new mines face threats from the militias who run the area, the report said.

Supply chain at risk

Global Witness said that its findings come amid a huge increase in demand for the minerals as production of green energy technologies ramps up. Sales of processed rare earth minerals for magnet productions are expected to triple by 2035.

The group warned of a high risk that the minerals are finding their way into the supply chains of major household name companies that use heavy rare earths in their products including Tesla, Volkswagen, General Motors, Siemens and Mitsubishi Electric.

Davis said the report’s findings demonstrate the need for the international community to broaden sanctions against the junta to include rare earth minerals.

“The disturbing reality is that the cash that is fuelling the environmental and human rights abuses caused by Myanmar’s rare earth mining industry ultimately stems from the global push to scale up renewables,” he said.

“As the climate crisis accelerates and demand for these low-carbon technologies skyrocket, today’s findings must be a wake-up call that the green energy transition cannot come at the cost of communities in resource-rich countries, and must instead be equitable and sustainable, prioritizing the rights of those who are most impacted.”

![Rare earth ores [left] are burned down before being transported from Kachin state to China. At right, sacks of rare earth ores await transport to China. Credit: Global Witness via AP](https://www.rfa.org/resizer/v2/3C3S4DRBHEYJSV6IFYAKT77ZTE.jpg?auth=0a6d9eb21d0f2a5d49c416183b2c9f37117fd1dbad7a0e22b634f59c66458349&width=800&height=263)

Global Witness called on companies to stop mining heavy rare earths in Myanmar and ensure that minerals from the country do not enter the global supply chain.

It also urged governments to impose import restrictions for rare earths produced in Myanmar, impose sanctions on armed actors illegally profiting from the industry, and introduce stronger policies to reduce the harms associated with extracting the minerals.

The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that about 240,000 tons of rare earth minerals were mined globally in 2020, with China accounting for 140,000 tons, followed by the United States with 38,000 tons and Myanmar with 30,000 tons.

Though China is the world's largest producer of rare earth minerals, it buys the ore from neighboring Myanmar, exploiting its cheaper labor.

Myanmar exported more than 140,000 tons of rare earth deposits to China, worth more than U.S. $1 billion between May 2017 and October 2021, according to China’s State Taxation Administration.