UPDATED at 3:25 P.M. ET on 2022-03-23

Citizens of Myanmar on Tuesday applauded the Biden administration’s recognition of their military’s deadly 2017 crackdown on the Rohingya minority as a genocide but questioned its timing and whether it will lead to concrete action against the junta amid ongoing rights abuses in their country.

On Monday, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced that American investigators had determined the Myanmar military was responsible for atrocities including mass killings, gang rapes, mutilations, crucifixions, and the burning and drowning of children during its offensive in Rakhine state, and said the acts constitute genocide under United Nations definitions.

Thousands died in the raids, which forced an exodus of more than 700,000 people to neighboring Bangladesh and followed a 2016 crackdown that drove out more than 90,000 Rohingya from Rakhine.

In a statement, the junta’s Ministry of Foreign affairs rejected the designation as “far from reality” and dismissed Blinken’s comments as “politically motivated and tantamount to interference in the internal affairs of a sovereign state.”

RFA's Myanmar Service spoke with several residents of Rakhine state who dismissed the U.S. determination as politically motivated.

Kyaw Kyaw Min, an army veteran from the Rakhine capital Sittwe, said that observers from the international community had chosen to ignore evidence to refute the allegations of atrocities and "criticize the internal affairs of another country without in-depth knowledge."

Aung Than Wai, a politician from Sittwe, questioned why the U.S. is applying the label of genocide to what he referred to as "a military operation" when it remains silent on "massacres" committed by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) insurgent group.

"They massacred over 200 Hindu and Marmas Buddhists who belong to the Rakhine ethnic group in 2017," he said of the ARSA, whose attack on government outposts in Rakhine that year led to the military crackdown on Rohingyas.

London-based rights group Amnesty International has said ARSA was responsible for killing "scores" of Hindus in Rakhine in August 2017, but maintains that the military's coordinated targeting of Rohingyas that year constituted an "unlawful and grossly disproportionate campaign of violence."

Monday's announcement also drew scorn from outspoken nationalist blogger Kyaw Swar, who slammed the U.S. in a post on the social media platform Telegram.

“We killed them. What can you do about it,” he wrote, suggesting that Washington “be quiet and concentrate on dealing with Russia” following its invasion of Ukraine.

Support for designation

Others applauded the decision and called on Washington to take further action against the military, which has killed at least 1,687 civilians and jailed 9,773 others since seizing power in a Feb. 1, 2021, coup.

Myanmar's shadow National Unity Government (NUG) welcomed the designation in a statement by Acting President Duwa Lashi La, who said his administration "acknowledges that discriminatory practices and rhetoric against the Rohingya also laid the ground for these atrocities."

"The impunity enjoyed by the military's leadership has since enabled their direction of countrywide crimes at the helm of an illegal military junta," he said, adding that "justice and accountability must follow this determination."

ARSA also issued a statement expressing gratitude to the U.S., and calling for the international community to hold the perpetrators of the 2017 violence accountable "so that repetition of such crimes may never be witnessed again."

Other sources in Myanmar told RFA they were pleased by Monday's announcement, but called it long overdue.

“These Rakhine state massacres were not the only ones committed by this army. Many have occurred in other ethnic areas as well,” said Win Aung, a resident of the commercial capital Yangon.

The junta is currently embroiled in multiple conflicts with armed ethnic groups and prodemocracy paramilitaries in the country’s remote border regions and reports have emerged of troops torturing, raping and killing civilians.

But while Western governments have ostracized and sanctioned the military regime, Win Aung said it is unlikely to step down without a fight.

“The whole world is now waiting to see what the U.S. will do,” he said. “Regardless of timing, I think this announcement will have an impact somehow. Especially at a time when the ICJ [International Court of Justice] is looking into the issue. I think it will hurt the junta’s defense at the ICJ genocide hearing.”

Gambia has accused Myanmar’s military leadership of violating the 1948 Genocide Convention in Rohingya areas in a case it brought to the Hague-based ICJ. The court is holding hearings to determine whether it has jurisdiction to judge if atrocities committed there constituted a genocide.

Su Myat, a young woman from Yangon, called the U.S. declaration “the right thing to do.”

But she said that the announcement should have been made long ago “because this kind of brutality has not only been directed against the Rohingya.

“They have committed many crimes everywhere, but these crimes only surfaced after the Rohingyas had their turn and that’s because [they were documented using] modern technology,” she said, noting that similar accusations of atrocities have been leveled against the military by members of the Kachin and Kayin ethnic groups.

Call for further action

Prior to Monday, the U.S. government had described the crackdown in Rakhine state as “ethnic cleansing” — not using the “genocide” designation, which carries more legal weight and which the Genocide Convention defines as “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group.”

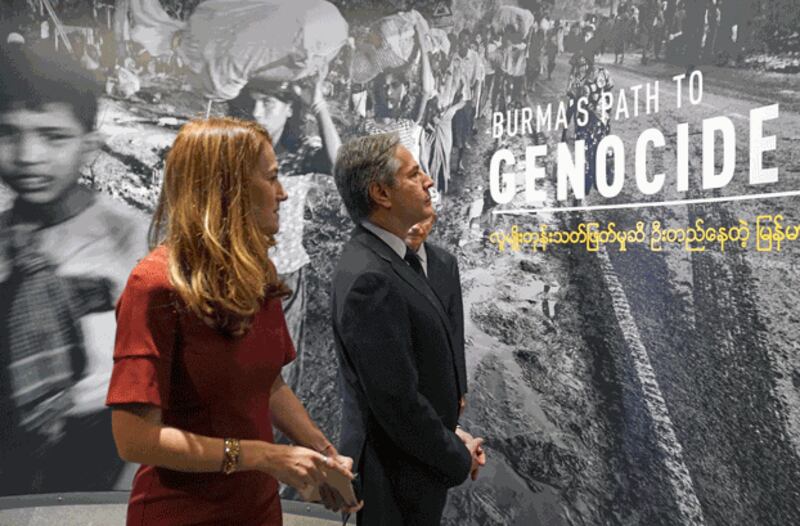

The new designation marks the eighth by the State Department since the Cold War, following its recognition of genocides in Bosnia (1993), Rwanda (1994), Iraq (1995), Darfur (2004) and areas under the control of ISIS (2016 and 2017), according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, where Blinken delivered his announcement on Monday.

Htet Myat Aung, a young man from Mandalay, said that the U.S. government’s declaration should mark the first step in a series of more significant and effective actions.

“All our people welcome the declaration of a genocide. But we hope to see more tangible and meaningful initiatives,” he said.

“People are now realizing that if the military can commit atrocities in cities like Yangon and Mandalay, where we have access to the internet and media, it must have been very bad in the remote areas where the Rohingya lived. Now we can sympathize with them and … we’d like to see more action on this issue.”

Htet Myat Aung said that while junta leaders may think that they can elude accountability by ignoring the international community, “they will have to pay for their crimes.”

Hope for the future

Myanmar, a country of 54 million people about the size of France, recognizes 135 official ethnic groups, with Burmans accounting for about 68 percent of the population.

The Rohingya, whose ethnicity is not recognized by the government, have faced decades of discrimination in Myanmar and are effectively stateless. They have been denied citizenship. Burmese administrations have refused to call them “Rohingya” and instead use the term “Bengali.”

The atrocities against the Rohingya were committed during the tenure of the civilian government of Aung San Suu Kyi, who in December 2019 defended the military against allegations of genocide at the ICJ. The Nobel Peace Prize winner and one-time democracy icon now languishes in prison — toppled by the same military in last year's coup.

A Rohingya named Hla Kyaw, who has lived in Thei-Chaung Muslim refugee camp in Sittwe since the 2016 and 2017 crackdowns, told RFA that he was saddened by the losses endured by his ethnic group as well as by people throughout the country.

“There are laws in Myanmar, but the laws have been ignored,” he said. “This should not have happened. We hope that we will enjoy freedom in the future and that life will improve for our children.”

Translated by Khin Maung Nyane. Written in English by Joshua Lipes.