Myanmar’s military is threatening to seize the homes of residents of a fishing village near one of its naval facilities if they refuse to relocate to a new location in the mountains, despite pleas from the villagers that such a move would upend their way of life.

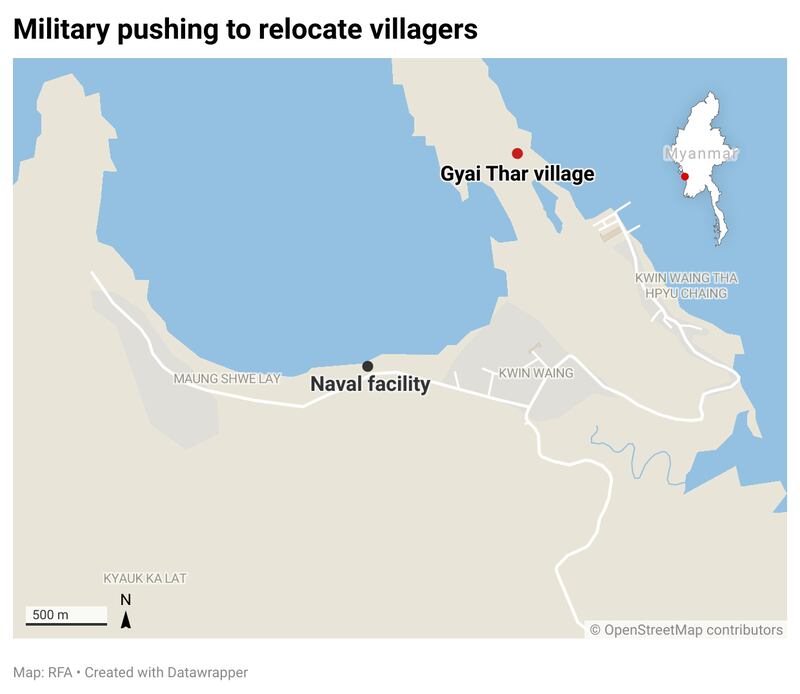

The 70 homes in Gyai Thar village lie about 1.5 miles from a diving and transport unit, about 21 miles south of a naval base at Thandwe in the western state of Rakhine, where renewed fighting between the junta and the Arakan Army armed ethnic group has intensified following the dissolution of a fragile ceasefire in July.

The military wants Gyai Thar’s 350 residents to move next month to a site chosen by the junta.

“They said we must move out, no matter what,” a villager who requested anonymity for security reasons told RFA’s Burmese Service. “We must leave no matter how many years we’ve stayed here. If we don't, they said they’d remove us by force.

“They said they have a project [they are working on]. They didn’t show any documentation of it. They seemed to be saying they have the power to do what they like. When they say go, we can just go,” the villager said.

The diving and transport unit lies only three miles away from Gyai Thar, according to the villager. He said that authorities had already requested that the village relocate once in 2018 and twice more prior to the Feb. 1, 2021, coup, but since last April the junta has been stepping up the pressure on the community.

The relocation zone has been prepared on a mountain range about four miles away from the village, but moving there would be hard for residents, who rely on the sea for food and their incomes, the villager said.

“They have a plan for relocation, but the site we are asked to move to is not suitable for people like us who mostly work as fishermen,” another Gyai Thar resident told RFA.

“They have not constructed any buildings for us. They just cleared the land and asked us to move there. So we can't do that. We are people who depend on the sea for food. It’s impossible for us to live in the mountains, about four miles from the sea,” the second villager told RFA.

Other villagers said that they have been living in Gyai Thar for generations, and any relocation zone must be close to the sea.

In a notice to the village in April last year, the military said the people in the community were living on government property without permission in violation of Section 3 of the 1955 Government House Eviction Act. It threatened that the villagers would be forcibly removed if they did not relocate before a specific date.

The military should at the very least offer compensation to the villagers, as well as a site near the sea, Oo Tin Nyo, a lawyer who assists citizens with land issues, told RFA.

“The place where they are asked to move is about four miles away, so it is difficult for people like them who live by the sea. Their livelihood will be in jeopardy,” he said. “I think it’d be more acceptable if the site is close to the sea, with roads constructed and power lines and water guaranteed along with some moving expenses.”

He said it’s a particularly hard time to move for the residents, given inflationary pressures in the country.

Khine Thuka, spokesperson for the Arakan Army, told an online news conference earlier this month that the junta is wrong to claim Gyai Thar village sits on military land.

“All those villagers have been living there since the time of their ancestors and now the military is saying that they must move out immediately despite the monsoon rains, which is an inhumane act,” Khine Thuka said. “It is an act of bullying people because they have weapons.”

RFA contacted Rakhine State Attorney General Hla Thein, spokesman for the Rakhine State military council, but he denied any knowledge of the situation.

In May 2021, junta troops removed nearly 200 houses and shops, with the help of a large number of police personnel, in the town of Ann where the junta’s Western Command Headquarters of Rakhine is located, saying they had encroached on military land.

Myanmar military and Arakan Army forces fought fiercely in Rakhine from December 2018 to November 2020 over the latter’s demand for self-determination for the state’s Buddhist Rakhine ethnic minority.

But the two sides struck an uneasy truce a few months before the military seized power from a democratically elected government on Feb. 1, 2021, and Rakhine had been quiet amid widespread protests and fighting against the coup and junta across the country of 54 million people.

Translated by Khin Maung Nyane. Written in English by Eugene Whong.