PHNOM PENH—Thirty years after the Khmer Rouge took power in Cambodia, the author of a new biography of Pol Pot describes the forced evacuation of Phnom Penh as a grim harbinger of the brutal years to follow—after an earlier, little-known evacuation of Oudong village in the north.

The evacuation of Phnom Penh “was chaotic, it was highly disorganized, and in a way it was a paradigm… emblematic of everything that would follow, because it was extremely harsh, extremely brutal,” Philip Short, whose book “Pol Pot: Anatomy of a Nightmare” was published in February, said in an interview.

"Pol Pot decided [to] abolish the idea of the city," Short said. "And that’s what happened, everyone was sent out, [and] at least 20,000 [people] died during the evacuation as a result of a muddle of incompetence and inefficiency."

"Pol Pot was basically leading a peasant rebellion, and peasant rebellions always regard cities as sinks of iniquity, of corruption," Short said, noting that the Khmer Rouge Central Committee had decided on the evacuation six or seven months earlier.

Politically, this was an extremely useful characteristic because he would be very persuasive, he would win people over, he would win their confidence, and behind this smile, there was an inhuman ruthlessness.

Pol Pot: Anatomy of a Nightmare"

"Finally, it was a security thing—if you send the urban population into the countryside you break up the networks, the united urban citizens, and you make it much more difficult for them to resist the new regime."

Trial evacuation of Oudong

In March 1974, the Khmer Rouge conducted a preliminary evacuation of Oudong village north of Phnom Penh that prompted the Khmer Rouge to go ahead and evacuate Phnom Penh as well.

“Oudong had been captured, and they had marched the citizens out into the jungle where some of them had been killed, those who were regarded as misfits, most of them intellectuals,” Short said.

“One of Pol Pot’s aides told me when I did these interviews that to them there hadn’t been many problems, they felt that the evacuation of Oudong had gone well, that it had saved the Khmer Rouge forces from being contaminated by ideology, and if that had worked at Oudong, this was something that could be done in the whole country which meant in Phnom Penh,” he said.

Welcomed by a war-weary population

When the black-clad Khmer Rouge overran Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975, many exhausted residents welcomed them, hoping it meant the end of Cambodia's civil war.

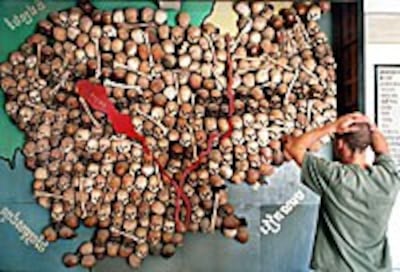

But within hours, Pol Pot launched his “Year Zero” campaign, emptying towns and cities and forcing city-dwellers to become slave laborers in the countryside. By some accounts, Phnom Penh’s population dropped from 2 million to 25,000 in just three days.

Charismatic and cruel

Short described Pol Pot as a highly charismatic “master of disguise,” whose warm demeanor concealed what eventually became a murderous disposition.

Pol Pot “did have a very engaging, attractive smile. When I first encountered him in Peking [Beijing] in 1977, that was one of the things that really struck you very forcibly, and it also struck many Cambodians,” Short said.

“Pol Pot was a teacher in Phnom Penh, in the late 1950s and early 60s. One of his students wrote that you only had to meet him once and you felt that this was someone who would be your friend for life,” he said.

“Politically, this was an extremely useful characteristic because he would be very persuasive, he would win people over, he would win their confidence, and behind this smile, there was an inhuman ruthlessness.”

Idealistic at the start

“It didn’t start out that way—I think he was genuinely altruistic, idealistic at the beginning, as were all that group who became Khmer Rouge leaders. Then a lot of circumstances came together which brought about the conditions in which he would...lead an extremely radically and extremely brutal revolution.”

Pol Pot’s radical ideas were imbued with some aspects of Buddhism, such as the rejection of property and emotional attachments, Short said. “It’s a nihilistic philosophy in some ways, but you see it repeated and repeated and repeated in Khmer Rouge documents,” he said.

Eluding justice

No Khmer Rouge leaders have yet been brought to justice.

Pol Pot himself, who fled the Vietnamese to wage a guerrilla war for the next 18 years from jungle along the Thai border, died in 1998, evading all efforts to bring him to justice.

But his top henchmen—including “Brother Number Two” Nuon Chea, former Khmer Rouge president Khieu Samphan, and ex-foreign minister Ieng Sary—remain alive and free, though the United Nations and the Cambodian government have raised most of the U.S. $56 million for a full genocide tribunal.