Recent developments in the South China Sea have highlighted the need for a legally-binding Code of Conduct for all competing parties in the disputed waters. Yet maritime analysts express doubt that such rules can be agreed any time soon.

China and countries from the Southeast Asian grouping ASEAN have been negotiating a Code of Conduct (COC) after reaching an initial Declaration of Conduct (DOC) of Parties in the South China Sea in 2002.

In 2018, ASEAN and Beijing managed to release the Single Draft Negotiating Text – or a draft agreement – and in July 2023 the two sides announced that they'd completed its second reading.

The third reading of the draft negotiating text is believed to have commenced in October 2023 and, according to a Chinese spokesperson, “the consultations on the COC are going smoothly.”

"Parties have adopted guidelines to accelerate consultations on the COC," said Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman Mao Ning at a recent news briefing. "The issue of the South China Sea is highly complex and faces external interference."

“We hope ASEAN countries will work with us toward the set target and speed up consultations for the early adoption of the COC.”

Chinese officials, and state-sanctioned academics, regularly point at the so-called “external interference” – a thinly-veiled reference to the United States and allies - as the main source of discord between Beijing and ASEAN.

"The biggest trouble in the South China Sea does not come from countries within the region but from external forces' disturbances, which attempt to turn the South China Sea into a sea of conflict and a sea of war," Song Zhongping, a Chinese military expert and TV commentator, was quoted by the tabloid Global Times as saying recently.

Major obstacles

China has submitted a number of provisions of the COC negotiating text that are clearly designed to stem any ‘external interference’, explained Carlyle Thayer, an emeritus professor of politics at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of New South Wales Canberra.

One of China’s provisions says parties in the South China Sea “shall establish a notification mechanism on military activities, and to notify each other of major military activities if deemed necessary,” according to Thayer.

“The parties shall not hold joint military exercises with countries from outside the region, unless the parties concerned are notified beforehand and express no objection,” the provision reads.

This provision would block any joint military exercises, bilateral or multilateral, between ASEAN countries and the U.S., as well as Japan and other regional powers, unless Beijing agrees to them.

ASEAN member Vietnam disagreed with this provision and submitted its own, asking for only a notification of any impending joint or combined military exercise to take place within the South China Sea. It said such notifications should be made 60 days before the commencement of such a military exercise, Thayer told Radio Free Asia.

Nguyen Hung Son, vice president of the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam, said ASEAN “would never agree to such terms.”

“For instance, the Philippines and Singapore will voice protest,” Son said.

Another stumbling block is the exploration of natural resources in the South China Sea.

“China proposed that oil and gas exploration and development in disputed waters shall be carried out through coordination and cooperation among the littoral states to the South China Sea, and shall not be conducted in cooperation with companies from countries outside the region,” said Thayer.

“To that, Malaysia counter-proposed a provision saying that nothing in the COC shall affect the rights or obligations of Parties under international law, including the rights or ability to conduct activities with foreign countries or private entities of their choosing,” he added.

These two contentious issues alone could prove difficult, even impossible, to resolve.

"China seems to have inserted this provision [on oil exploration] in an attempt to coerce other countries into signing joint development agreements with Chinese companies," regional analyst Ian Storey wrote in a publication by Singapore's ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.

“The Southeast Asian claimants view this gambit as an egregious violation of their sovereign rights under UNCLOS,” he said, referring to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

“But it is hard to see how China would agree to drop this provision because to do so would fundamentally undermine its own jurisdictional claims.”

Blame game

In light of recent tensions in the South China Sea, especially between China and the Philippines over a couple of atolls that lie within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone, Beijing seems to put the blame on Manila.

The Chinese Communist Party's publication China Daily this week published an opinion article which slammed Manila's efforts to resupply its military outpost on the Second Thomas Shoal, calling it a "dishonest approach" and a violation of international law.

“The Philippines’ choice is not only crucial to the comprehensive, effective and faithful implementation of the DOC, but will also have a long-term impact on the ongoing consultations on the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea and the effective application of the COC in the future,” reads the article.

The hawkish mouthpiece Global Times, for its part, alleged that “the Philippines has been calculating something new – it now believes that standing absolutely in line with ASEAN no longer brings itself maximum interest.”

“The Philippines wishes to strive for more interests for its own in the third reading of the COC text, by continuing to coordinate with the U.S. in its Indo-Pacific Strategy,” the paper said.

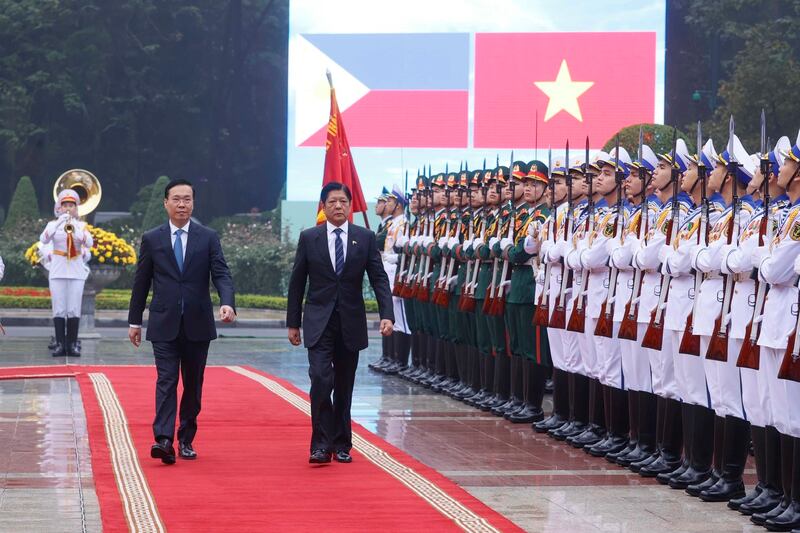

Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos indicated on several occasions that his country may seek to form bilateral codes of conduct with neighboring countries to prevent incidents at sea. Marcos recently visited Hanoi, where he and Vietnamese leaders agreed in principle on maritime cooperation.

Although Hanoi, due to its so-called “bamboo diplomacy,” would not want to be seen as taking sides in any dispute, the agreement will no doubt be deemed by Beijing as an attempt by Manila “to forge its own clique in the South China Sea,” the paper said.

With stark differences remaining on the most critical issues, it’s hard to see how the China-ASEAN COC negotiations are “going on the right track with its own pace” and “the conclusion of the COC is not far away,” as claimed by Chinese officials.

“Back in July last year, ASEAN and China committed to concluding a COC within three years but I'm still skeptical,” said Bill Hayton, associate fellow in the Asia-Pacific Program at the think tank Chatham House in the United Kingdom.

“I think this is one of those efforts from China to try to talk up the COC and make it seem like it’s inevitable so as to roll over any opposition to the Chinese side's preferred version of the text,” Hayton added.

Edited by Mike Firn and Taejun Kang.