Updated July 14, 2024, 06:16 a.m. ET.

Britain’s new ruling party has pledged a thorough audit of U.K.-China relations to establish a clearer long-term China policy, including its dealings with Beijing over the South China Sea and Taiwan, but analysts say little change is likely in the near future.

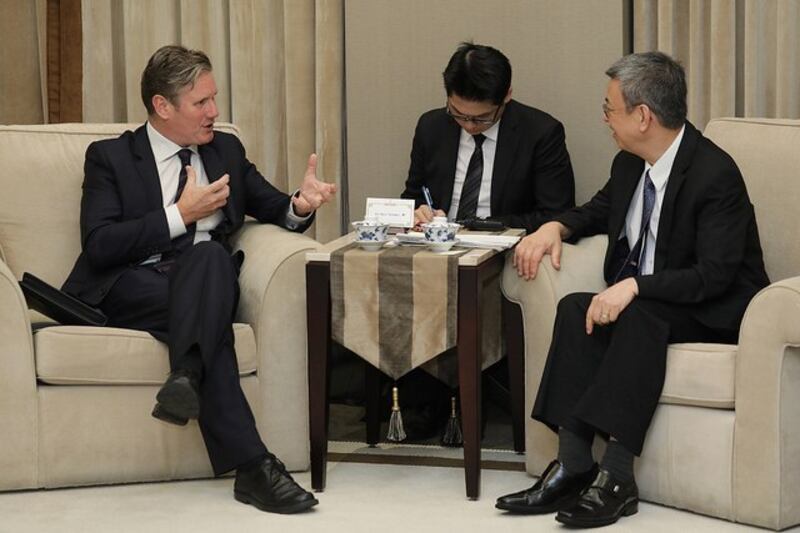

Keir Starmer’s Labour party won a landslide victory in last week’s general election, ending 14 years of Conservative government.

U.K. policy has been that it “takes no sides in the sovereignty disputes in the South China Sea, but we oppose any activity that undermines or threatens U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) authority – including attempts to legitimise incompatible maritime claims,” in the words of Anne-Marie Trevelyan, minister of state for Indo-Pacific under Prime Minister Rishi Sunak.

Trevelyan reiterated that London’s commitment to the UNCLOS was “unwavering” as it played a leading role in setting the legal framework for the U.K.’s maritime activities.

“It's a standard position on upholding international law, freedom of navigation and the rules-based order,” said Ian Storey, Senior Fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, “This is not going to change.”

However, with China’s increased assertiveness and growing military might, upholding those principles in distant waters will be a challenge. Furthermore, there are Britain’s own interests in economics, security and geopolitics to be considered.

In 2021, the British government announced an overhaul in its foreign policy - Global Britain in a Competitive Age - which emphasized a "tilt to the Indo-Pacific" that, following in the footsteps of the U.S., promised a bolder strategic presence in the region where China is looming large. In 2022, Britain released a new National Strategy for Maritime Security, with one of the main focuses being the South China Sea.

Yet there has not been any major British deployment in the region since 2021, and the Royal Navy did not send a warship to take part in the ongoing U.S.-led RIMPAC - the world's largest international maritime exercise.

It remains unclear how Britain will pursue its maritime ambitions in the Asia-Pacific, especially when overall policy towards China has been deemed inconsistent.

‘Clear steer’ in dealing with China

Labour’s promise to conduct both a defense review and an audit of China policy “leaves many questions unanswered,” said Gray Sergeant, research fellow at the Council on Geostrategy, a British think tank.

“Initially, Labour was skeptical about the 'tilt to the Indo-Pacific', however, they have supported measures which have stepped up Britain's defense role in the region,” Sergeant told RFA.

“It is very unlikely such advances will be reversed, the question is whether a Labour government will be inclined to build on these steps if, as it seems, attention is focused on enhancing the U.K.'s role in European security,” the analyst said.

RELATED STORIES

[ Not so hard: British scholar proposes fix for South China Sea disputesOpens in new window ]

[ US, UK aircraft carriers lead show of naval might around South China SeaOpens in new window ]

[ With eyes on Beijing, US and Japan pledge stronger tiesOpens in new window ]

Another China expert, veteran diplomat Charles Parton, said that in the past Labour “has not said things which indicate that its China policy will be different from that of the Conservatives.”

“But the latter's strategy was never articulated, for which they came in for justified criticism,” said Parton, senior associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute. “The pressure now is on Labour to give a clear steer and to ensure consistent implementation across the various government departments whose interests involve dealing with China.”

The Conservative government recognized China as a “systemic challenge”’ that it sought to counter with a three-stranded strategy of “‘protect, align, engage.” Labour’s new foreign secretary, David Lammy, proposed a similar “three Cs” (compete, challenge, cooperate) in dealing with China.

“That signals continuity,” said Gray Sergeant. “The question is which of these three strands will take precedence?”

The analyst noted that Lammy put particular emphasis on cooperation and engagement, and seemed keen on more ministers visiting China, which was Britain’s fifth-largest trading partner in 2023, according to the U.K. Department for Business and Trade.

Some activists, like Luke de Pulford from the U.K. Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China, said that the new British government was likely to champion trade over thorny issues that would cause discord.

“Labour needs to deliver on the economy and is scared that upsetting Beijing would jeopardize that goal,” de Pulford wrote in a recent opinion piece.

“Ministerial ambition, parliamentary trench warfare, media outrage or unavoidable circumstantial change can all shift policy, but outside of a serious escalation in the South China Sea, I don't see it happening,” the human rights activist wrote.

But another activist said that Labour's manifesto made clear “their intention to bring a long-term and strategic approach to managing relations with China.”

“This could lead to a more robust stance on human rights abuses in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, and increased support for Taiwan's autonomy,” said Simon Cheng, a Hong Kong democracy activist in London.

“However, we must watch closely how these words translate into actions,” Cheng warned.

What does China say?

China has been closely following developments in U.K. politics, with Premier Li Qiang sending a congratulatory message to Starmer almost immediately after he became Britain's prime minister on July 5.

Li said that China and Britain were both permanent members of the U.N. Security Council and cooperation between them “not only serves the interests of the two countries, but also is conducive to the unity of the international community in addressing global challenges.”

Starmer, as a member of parliament and shadow Brexit secretary, visited Taiwan in 2016 and 2018 to lobby against the death penalty. Observers say it’s very rare that any top British leader has had an experience of Taiwan, which Beijing considers a Chinese province that must be reunited with the mainland.

While the issue of Taiwan has not emerged in bilateral interactions, British politicians in the past have angered China over their statements about Hong Kong and the South China Sea.

A Foreign Office spokesperson’s statement criticizing the “unsafe and escalatory tactics deployed by Chinese vessels” against the Philippines in the South China Sea earned a rebuke from Chinese diplomats in London, who said they “firmly oppose and strongly condemn the groundless accusation made by the U.K., and have lodged stern representations with the U.K. side on this.”

China maintains that almost all of the disputed South China Sea and its islands belong to it. China refused to accept a 2016 arbitral ruling that rejected all its claims in the South China Sea but it recognized that Britain’s stance of not taking sides in the South China Sea issue had changed.

Before 2016, the U.K. did not have a clear-cut South China Sea policy, wrote Chinese analyst Liu Jin in the China International Studies magazine.

Liu argued that Britain’s change in policy, as well as its stance in the South China Sea, were largely influenced by the United States.

“However, due to the security situation in its home waters, inadequacy of main surface combatants, and pressure of the defense budget, the U.K. will find it hard to expand the scale of Asia-Pacific navigation,” he said, adding that London also lacks the willingness to step up provocation against China.

Edited by Mike Firn.

Updated to correct Ian Storey's title to Senior Fellow.