When Sakina Batt, a young Tibetan Muslim from Nepal, wrapped up a four-year job working with the Tibetan government in exile in Dharamsala, India, she received a rare honor: an audience with the Dalai Lama, spiritual leader of the Tibetans.

“I completely broke down when I entered the room,” she said. “The environment was such and the vibe was such that even though it was just a virtual audience, I felt so special.”

“Just because I’m a minority, just because I’m a Tibetan Muslim who worked at the administration, I was given that opportunity,” added Batt.

“Most people don’t know about the existence of the Tibetan Muslims,” she told RFA’s Tibetan Servce.

“Religion, of course, is the only difference between devout Muslims and Tibetan Buddhists,” she told RFA. “Other than that, everything is the same. We have the same culture, we have the same traditions and language, what we eat is the same, and what we wear is the same.”

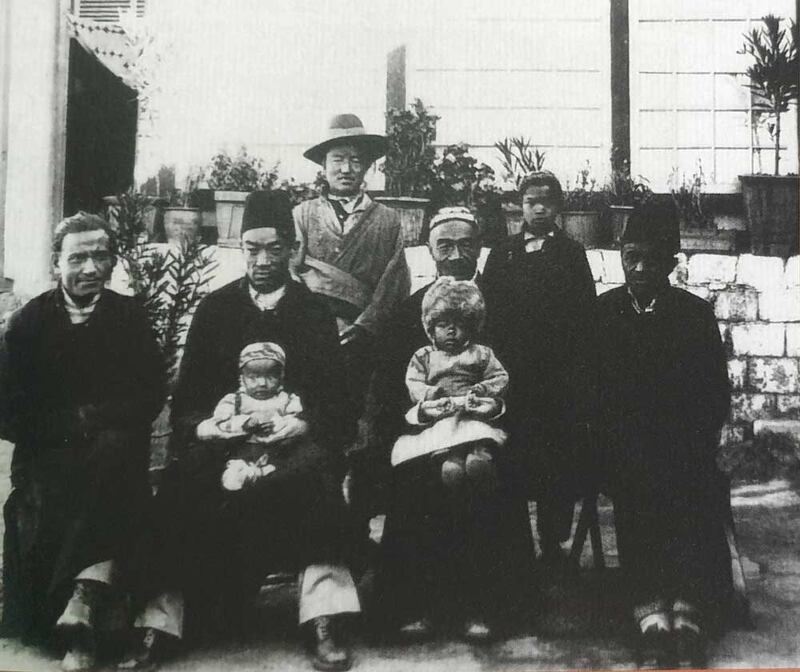

Batt, 30, hails from a community whose origins date at least to the 14th century, when Muslim merchants from Nepal, China, Kashmir and Ladakh began settling in Tibet, according to information on the website of Tibet House U.S., a Tibetan cultural institution based in New York.

The migrants intermarried with Tibetan Buddhist women, who then converted to Islam, while adopting Tibetan language and customs.

By the 16th century, these Tibetan Muslims, now known as Khache, formed an integral part of Tibet's golden age, according to David Atwill, a history professor at Pennsylvania State University who wrote about Tibetan Muslims in his 2018 book Islamic Shangri-La: Inter-Asian Relations and Lhasa's Muslim Communities, 1600 to 1960.

“In the [Tibet Autonomous Region], most of the Khache have, when forced to choose their officially designated ethnicity … have identified themselves as Tibetan even as they continue to believe in Islam and attend daily prayers at the local mosques,” Atwill wrote in an email.

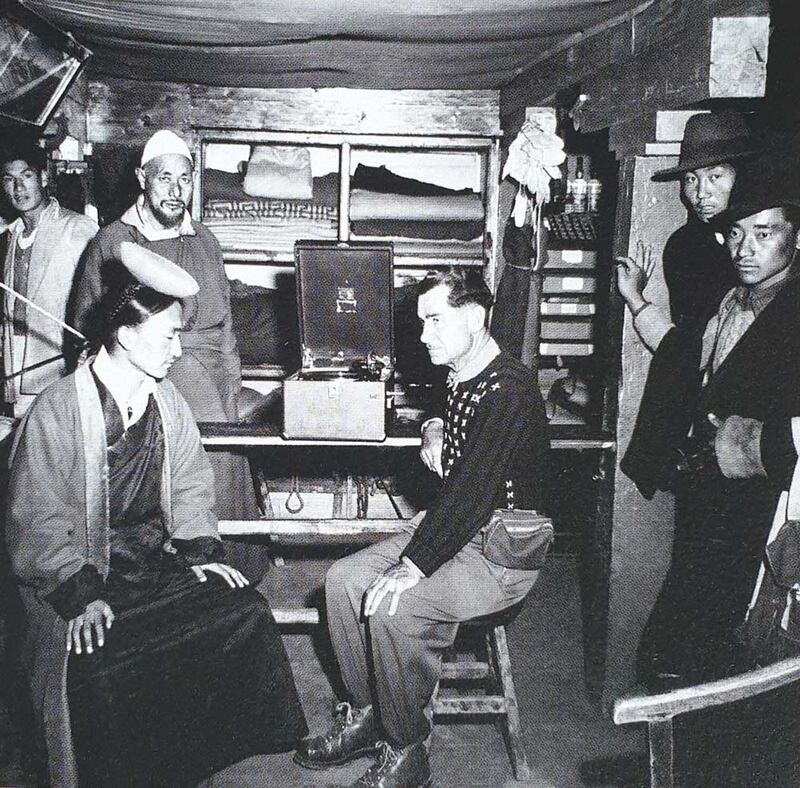

After China took over Tibet in 1950 and the Dalai Lama fled to Dharamsala nine years later, many Tibetan Muslims left the region for neighboring areas to preserve the religion and identity they felt were threatened in communist China.

Their biggest community lives in Kashmir, but smaller pockets can also be found in Darjeeling and Kalimpong in the Himalayan foothills of India's West Bengal state, and in Kathmandu, Nepal, where 120 Tibetan Muslim families live, according to a May 2018 article in the Nepali Times.

They were granted citizenship by India due to the Kashmiri roots. Today, Tibetan Muslims form a very small minority in Tibet.

In the Tibet Autonomous Region, Muslims worship at least five mosques in the capital Lhasa area and exist peacefully with Buddhists, Atwill said.

“Like their Buddhist Tibetan brethren, the Tibetan Muslims face an array challenges to maintaining their Tibetan identity, maintaining fluency in the Tibetan language with the younger generation and identifying ways to promote their Tibetan identity in politically difficult times,” he wrote.

“While in the TAR, they continue to struggle to straddle the ethno-religious divide between being Tibetan and Muslim, when being Muslim is equally assumed to be Hui (not Tibetan),” he said.

Atwill said the Chinese likely chose to treat Tibetan Muslims differently than Uyghurs out of “cautious convenience” and a desire to not drive the Khache into a “common allegiance with the ethnic Tibetan majority,” many of whom want independence from China.

“That said, the Khache, like Muslims across China, remain vigilant and concerned about the stark anti-religious turn of recent policies,” he said.

Under leader X Jinping, China has mounted a campaign to “Sinicize” religion and make adherents place their loyalty in the ruling Chinese Communist Party.

To Tibet’s north in Xinjiang, an estimated 1.8 million predominantly Muslim Uyghurs and other Turkic minorities have been incarcerated in an extensive network of internment camps where they are subject to violence and forced labor.

The current Dalai Lama visited the Tibetan Muslim community in Srinagar, Kashmir, in 2012, regularly receives their representatives, and has participated in inter-religious events, said José Cabezón, the Dalai Lama professor of Tibetan Buddhism and Cultural Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

“The Dalai Lama considers Tibetan Muslims an integral part of the Tibetan people, and has tremendous respect for their history and culture,” said Cabezón.

Reported by RFA's Tibetan Service and Roseanne Gerin. Translated by Tenzin Dickey. Written in English by Roseanne Gerin.