Authorities in northwest China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) have detained an ethnic Uyghur who is a citizen of Afghanistan, according to members of his family who say they have called on Kabul’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs to assist in advocating for his case.

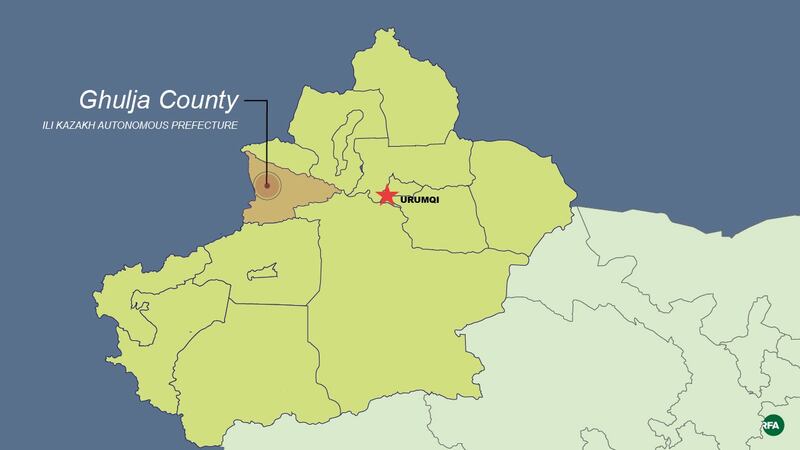

Abdughopur Abdureshid was born in Kabul, Afghanistan in 1988, but his parents moved the family to Ghulja (Yining) city in the XUAR’s Ili Kazakh (Yili Hasake) Autonomous Prefecture two years later to flee civil war.

His Virginia-based aunt, Hurshida Hasan, told RFA’s Uyghur Service that she learned during a recent trip to visit relatives in Turkey that Abdughopur Abdureshid had been detained in 2017, as part of a campaign of extralegal incarcerations in the XUAR that has seen up to 1.8 million Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities held in a vast network of internment camps since its launch earlier that year.

“When I went to Turkey, I met with a young man named Arapat Yadikar,” she said.

“I asked him about my family, the people who’d come from Afghanistan. He said Abdughopur had been his classmate [in Ghulja]. He said they took him into a camp in 2017.”

Hasan, whose own family had moved to Ghulja from Afghanistan in 1989 to escape the war, said Abdughopur Abdureshid had owned a shop repairing computers and “was always a very sickly, physically weak boy.”

Hasan said she also learned from relatives in Turkey that Abdughopur Abdureshid’s mother, Aynisahan Akbar, had died in Ghulja earlier this year.

Fleeing violence

Abdughopur Abdureshid’s family, along with Hasan and her family, had initially moved from Ghulja to Afghanistan in 1970 and became naturalized soon after.

“We were Afghanistan citizens—when the war in Afghanistan started, we all decided to head back to our homeland,” she said.

“[The Chinese government] wouldn't give us a visa and were always coming after us. We would have to go once every three months [to register]. This wouldn’t do, so ultimately, we went to a U.N. office in Beijing. We explained that the situation in Afghanistan was absolutely awful and we couldn’t go back there.”

On Feb. 5, 1997, protests sparked by reports of the execution of 30 Uyghur independence activists were violently suppressed by authorities in Ghulja, leaving nine dead, according to official media, though exile groups put the number at as many as 167.

Hasan said that after what became known as the Ghulja Incident, she and her family decided it was no longer safe to stay in the region and took advantage of their Afghan citizenship to leave China, first settling in Central Asia and later relocating to the U.S. Abdureshid’s family remained in Ghulja.

“We lived in fear afterward,” she said. “Our children were [teenagers] at the time. Many of the young kids in our neighborhood were detained. I didn’t want to have to deal with this, and so I left [that same year].”

Losing contact

On July 5, 2009, three days of unrest took place in the XUAR capital Urumqi between Uyghurs and Han Chinese that left some 200 people dead and 1,700 injured, according to China’s official figures. Uyghur rights groups say the numbers are much higher.

Hasan said that in the aftermath of the incident, authorities implemented strict security measures and contact with her brother’s family became difficult.

“When we called them, they were really uneasy, and we could sense that they were a bit angry,” she said.

“They said it very directly. On July 15, 2009, I called my older brother [Abdureshid] and asked to talk, because I suspected something was up. He said to me, ‘Little sister, it would be best for you to please not call us anymore. We’re living very well.’”

Since the internment campaign began in 2017, Hasan said, she had not spoken with her brother or any of the seven family members that remained in Ghulja.

“I didn’t even know that [my brother’s] wife had passed away,” she said. “I went to Turkey and learned about it there.”

In search of information

Abduletip Abdureshid, one of Abdughopur Abdureshid’s older brothers, currently lives and studies in Turkey. Since learning of his brother’s disappearance from his aunt, Abduletip Abdureshid has attempted to contact the Turkish government and the Chinese embassy in Ankara in search of information.

“Once it was clear that he was in a camp, I wrote emails to the Chinese consulate in Istanbul and the Chinese embassy in Ankara looking for my brother—requesting information about his whereabouts and whether he’s still alive,” he said.

In July, two months after his emails, a representative of the consulate in Istanbul responded, informing him “Abdughopur Abdureshid was detained for violating Chinese law. He is in good health.”

However, the reply contained no information about which law he had violated, what his sentence is, or at which internment camp he is being held.

“Later I wrote them another letter asking if he was really in a camp, if he’d really done something in violation of law, didn’t we have the right to know exactly what Chinese law he was being held on and to obtain information about what happened to him,” Abduletip Abdureshid said.

“It’s been two or three months and I still haven’t gotten a reply.”

Abduletip Abdureshid and his aunt believe that Abdughopur Abdureshid is guilty of nothing other than “being Uyghur.”

Government assistance

Abduletip Abdureshid also stressed that his entire family, including his parents, are Afghan, not Chinese, citizens.

From 1990 to 1995 they were required to renew visas each year so that they could live in China. After 1995, they were able to obtain permanent residency in China but because the situation in Afghanistan was so dangerous, they were unable to return to the country to renew their passports and other paperwork.

“At the time there was a policy in China for migrants who were returning to China [after having left for other countries],” he said.

“We were able to take advantage of that policy and become Chinese residents, but we were not full citizens.”

Abduletip Abdureshid said he has left messages with the Embassy of Afghanistan in Turkey seeking government assistance in advocating for his brother’s case but has yet to receive a response.

“I’m looking into [whether we have rights as Afghani citizens], but I haven’t found much because of the [coronavirus] pandemic,” he said.

“But I’m looking into it, and if we still have those rights, we will try to use them.”

Reported by Mihray Abdilim for RFA’S Uyghur Service. Translated by Elise Anderson. Written in English by Joshua Lipes.