The 12-year old Uyghur girl, who now lives in the U.S. state of Virginia, was about seven years old and starting to absorb a bit more knowledge when she first learned about the repression of Uyghurs in their homeland northwestern China’s Xinjiang region.

As she got older, her mother would tell her more and more about the back story, bringing it up in the normal course of conversation or if they were in the car and the girl asked a question about her grandparents still in Xinjiang.

“I felt really sad,” the girl said about when her parents starting telling her about the crackdown.

The girl, who spoke on condition of anonymity and did not want to identify her parents to avoid endangering relatives in Xinjiang, said that the pain hit home with her when schoolmates would talk about where they were from originally.

When the girl thought about her family coming from Xinjiang, other questions would arise, such as why her grandmother would never come to visit her family in the U.S.

Her voice grows weaker and begins to trail off whenever she is asked about her hometown.

“It does affect my voice,” the girl told RFA. “Sometimes if people ask me where I’m from, it’s going to be sometimes difficult because they don’t know much about us [Uyghurs], and because they think that China is like a perfect place. They don’t know about the government and everything.”

“They’re going to think you’re crazy, she added.

It’s never easy for teenagers and children to discuss tragedies in their families, nor is it easy for parents to broach such topics with their offspring.

Uyghurs, who are being persecuted as an ethnic and religious group by the Chinese government, face a common challenge of figuring out how best to talk with young people about the 21st-century atrocities occurring in China’s northwestern Xinjiang region.

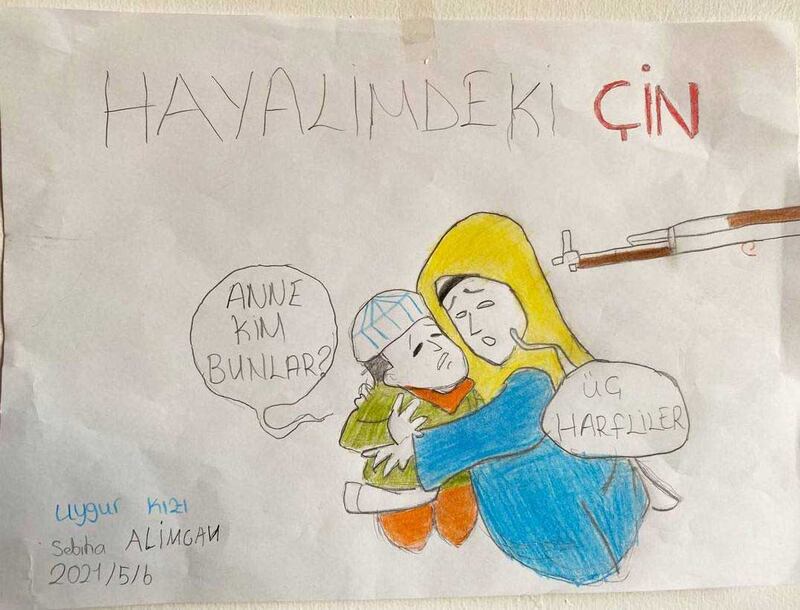

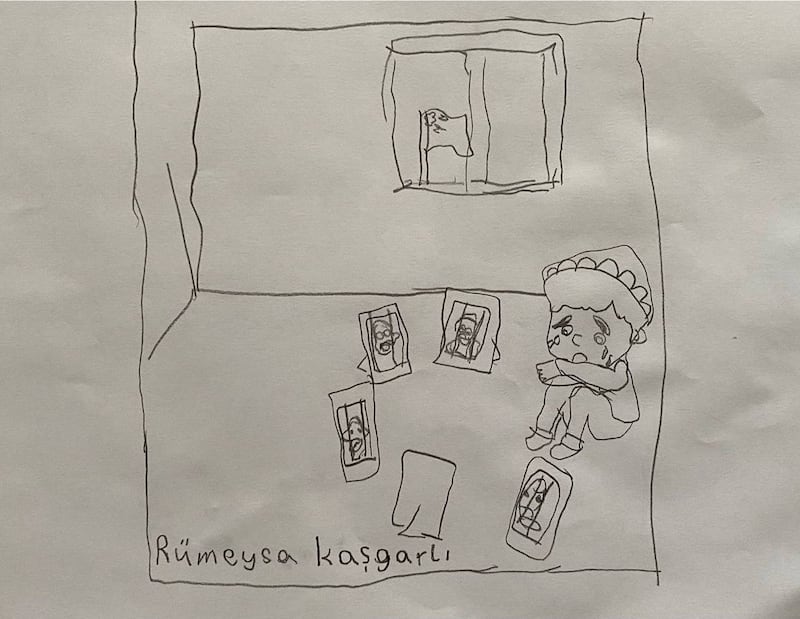

Uyghur children, born and raised in the diaspora, are asking their parents why they can’t see their grandparents, why Uyghurs in Xinjiang face genocide, and why they can’t visit their homeland.

Uyghur adults living abroad, frustrated by the inability to stop the atrocities despite widespread and credible reports about right abuses those living in Xinjiang face, say they are unsure about how to discuss the genocide with their children and sometimes falter when asked why it is happening.

At least 1.8 million Uyghurs and other Turkic minorities are believed to have been held in a network of detention camps in Xinjiang since 2017, purportedly to prevent religious extremism and terrorist activities.

Beijing has said that the camps are vocational training centers. The government has denied repeated allegations from multiple sources that it has tortured people in the camps or mistreated other Muslims living in Xinjiang.

The United States and parliaments of several Western countries have declared that China’s repression and maltreatment of the Uyghurs amount to genocide and crimes against humanity.

What should they be told?

Although children’s questions may seem simple to parents, what they are actually asking is about the history of Uyghurs, Chinese politics, and how to ensure the existence of Uyghurs abroad, said Suriyye Kashgary, co-founder of Ana Care, a Uyghur language school in northern Virginia with about 100 students ranging in age from five to 15 years old.

“They always ask questions like “Why isn’t my grandma here? Why isn’t my grandpa here? Where are my relatives? My grandpa isn’t around. My grandma isn’t around. Where are my relatives?” she said

“What I’ve been able to learn is that [many of] the children are a bit confused because some parents answer their kids’ questions, while some parents don’t speak with them in much detail at all,” she said.

While some Uyghur parents do not disclose information to their children about the genocide, others do talk about it and take them to local demonstrations against China’s repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

“There are many disagreements over whether it’s OK to explain some things to the children or not,” Kashgary said. “Some people argue that we shouldn’t let [the genocide] negatively impact their psyches, that children shouldn’t be sad about these things, and that they shouldn’t live under such stress from a young age.”

At her school, Kashgary expects teachers to be comprehensive, balanced, and vigilant as they work with the children, given the teachers’ need to be well-informed on a range of topics, she told RFA.

Uyghurs in the diaspora, who are indirect victims of China’s genocide, have been demanding justice by exposing the oppression of their families to others, including to the media.

But as a collective group of genocide victims, they have not been able to fully shield their children from the emotional suffering and negative psychological influences of the ongoing atrocities targeting Uyghurs.

Zubayra Shamseden, four of whose family members were killed or tortured by the Chinese government as part of the Ghulja Massacre in 1997, and who has relatives currently being held in internment camps in Xinjiang, works as China’s outreach coordinator for the Washington-based Uyghur Human Rights Project and as a Uyghur human rights activist.

“When it comes to the Uyghur genocide, it’s a fact that it is tearing up and impacting the lives of Uyghurs on the outside in the diaspora as well,” she said. “It’s not just adults — the shadows of the Uyghur genocide are affecting children and teenagers.”

Shamseden says that Uyghurs in the diaspora are dealing with a kind of emotional genocide and that trying to hide the genocide from the children will not solve the issue.

“It is likely only those parents who are unable to accept [the genocide] psychologically or deal with it properly themselves who worry that letting their children know about it may place undue psychological pressure on them,” she said. “In fact, children can learn about [genocide] in many different ways.”

Shamseden’s children, who were born and raised outside Xinjiang, also have become activists, participating in events protesting the Chinese government’s crackdown on Uyghurs.

“Parents have a responsibility to show children the way, lead them down [the right] paths, take them to proper activities,” she said.

Part of their identity

Kashgary, who has been a Uyghur language instructor for nine years, believes that understanding the widespread atrocities and genocide is an important part of Uyghur children learning about their identity and the world.

It is important for Uyghur children to learn about their history, culture, and the current situation in Xinjiang so they can understand the challenges facing their families and the ethnic group as a whole, she said.

Kashgary said she takes extra care to ensure that classroom instructors avoid encouraging racism or hatred when discussing difficult and sensitive topics like genocide and to provide students with scholarly, fact-based materials.

Uyghur language schools around the world all face the obstacle of how to educate children about the genocide with a lack of standardized materials and appropriate manuals for the student’s psychological well-being.

Teaching Uyghur children about genocide is a difficult task for educators and parents alike.

Nevertheless, it is important to raise Uyghur children in the diaspora so that they know about the genocide facing Uyghurs, they are taught to support Uyghur activism, and work in support of human, social, and political rights, Shamseden said.

Testimonies by Uyghurs who have been detained in internment camps but later freed have been particularly influential in the global response to the crisis.

Camp survivors have real-life experience in understanding the psychological impact of the genocide and its effect on victims’ families, including children.

Gulbahar Haitiwaji, who was detained in one of the camps but now lives in Paris, said she has never hidden the brutal, abusive treatment she experiences from her daughters and that she takes every opportunity she can to tell her story.

“The Chinese [authorities] told me I couldn’t speak about anything, that if I said anything my relatives in the homeland would end up threatened and in danger, that I needed to think about the people who were going to stay behind in the homeland,” Haitiwaji said.

But Haitiwaji noted the importance of speaking about the horrors of the camps as China wages a disinformation campaign to whitewash and justify the genocide, and said that Uyghur parents must protect their children from the propaganda by telling them the truth.

“Even now — more than two years since I came here — whenever we’re eating or drinking tea, if some words or movements come up that remind me of the camp, I immediately, at the right moment, tell the story,” she said. “I talk about the situation. I haven’t hidden anything.”

“Look at the slanderous things the Chinese government is writing about us,” she said. “Of course, if I don’t explain things to my kids, I wonder whether they’re going to believe the slander.”

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokespeople have dismissed reports about the genocide of the Uyghurs as the “lie of the century” and denied all accusations of human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

All Uyghur parents must tell their children about the genocide and rights abuses occurring in Xinjiang, Haitiwaji said.

“If we don’t tell them, they’re going to know nothing about the oppression our people are facing,” she said. “They might even come to believe the brainwashing lies of the Chinese government.”

Upstanders, not bystanders

Psychologist Nechama Liss-Levenson, who has a private practice in Washington, D.C., has published numerous scholarly articles on family relationships and how children deal with trauma and loss.

She recently began taking part in the Uyghur Wellness Initiative, a collaborative program sponsored by groups including the Uyghur Human Rights Project and Uyghur American Association, to treat and prevent the effects of genocide on the mental health of diaspora Uyghurs.

“The Uyghur genocide affects every Uyghur,” she said. “We all know it’s not easy to teach kids about genocide and other terrible tragedies.”

Such discussions cannot be one-time events, but rather part of ongoing conversations along with teaching children about what they can do so they do not feel powerless, she said.

“One thing that I think is important is to teach children about resilience and activism — without using these words — so that they don’t feel completely helpless,” Liss-Levinson said. “One of the things that you might teach them — not all at once but over many conversations at different ages and stages — is that in their lives here at school, they should be upstanders and not bystanders.”

Thomas Wenzel, an associate professor of psychiatry at the Medical University of Vienna in Austria who has conducted research on the effect of the Uyghur genocide in exile communities, said Uyghur parents in the diaspora struggle to deal with the genocide as well, wondering what has become of relatives in Xinjiang and despairing over shortcomings in efforts by the international community that have not yet ended the repression.

“When parents are distressed, it is more difficult for them to focus on the children. … The children feel it, and they feel abandoned,” he said.

Wenzel suggests that Uyghur diaspora communities collectively tackle the issue.

“It’s important that it’s a community process,” he said. “From psychology and psychiatry, we know now that if something very bad like genocide or war happens, it’s very important that the community starts the process to confront integrate what has happened, that there is a community project.”

Wenzel cited the example of communities in Myanmar where traditional storytellers with hand puppets acted out negative events, followed by group discussions.

“They brought it out into the open, and there was a space to work on it,” he said. “It’s important that this is by the whole community so that everyone is supporting each other, and no one is left alone.”

Translated by RFA’s Uyghur Service. Written in English by Roseanne Gerin.