On a cold winter day 25 years ago, young Uyghurs in the western Chinese city of Ghulja (in Chinese, Yining) staged a protest to call for an end to religious repression and ethnic discrimination.

The events of that day would instead come to be known as the Ghulja Massacre of 1997, an incident that Uyghurs now look upon as a harbinger of an even greater level of persecution and violence against the largely Muslim community in China that has unfolded in stages since then.

As many as 200 hundred people may have been killed in the massacre — one report said thousands may have died — but it received little international attention at the time.

As much of the world’s attention is drawn to China for the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing, Uyghurs are using the anniversary of Ghulja to press for an international investigation into what transpired that day and to seek accountability for those behind the bloodshed.

“Twenty-five years ago, the Ghulja Massacre was exemplary of the treatment of the Uyghur people by the Chinese authorities and its crackdown on freedom of expression and assembly,” said Dolkun Isa, president of the World Uyghur Congress (WUC), in a statement issued Feb. 4. “Now, the Chinese government’s genocidal policies are ensuring to prevent the Uyghur people from ever speaking out again.”

Today, nearly 2 million Uyghurs are thought to have been sent to mass internment camps in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region by a government desperately trying to maintain control of an ethnically and religiously diverse population.

On Feb. 5, 1997, the crowd had gathered to protest a prohibition of Uyghur social gatherings known as meshrep, a celebration of the community's culture and traditions.

But the protesters were met by Chinese security and armed forces who used water cannons to disperse the crowd. When that didn’t work, they then used their guns, according to witnesses.

The Chinese government at the time claimed that only 10 people died during the protest. Its official organ called the protestors “insurgents.”

But Uyghur organizations and international rights groups later said at least 200 demonstrators were killed. Thousands of others were arrested.

Gaining the upper hand

China has continued to hunt down Uyghurs connected to the incident. Many arrested for participating in the protest and in other demonstrations ended up in China’s “re-education” camps — what Uyghurs say are concentration camps.

China began its mass internment campaign in the region in 2017. An estimated 1.8 million mostly Muslim Uyghurs and other Turkic minorities are believed to have been detained in an extensive network of hundreds of camps since then.

Witness testimonies and investigative reports have since alleged that the Chinese government has tortured detainees, sterilized Uyghur women, and conscripted Uyghurs for work in factories.

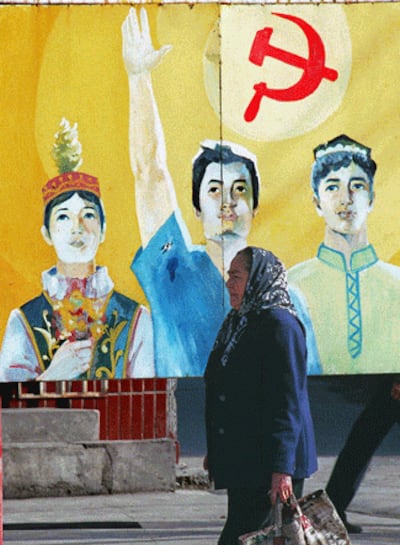

A year before the Ghulja Massacre, the Chinese Communist Party’s Politburo issued the “No. 7 Document” outlining measures to prevent the rise of religious and ethnic extremism. It called on law enforcement to suppress any independence movements. Many Uyghurs want Xinjiang to break away from China and to form a new country called East Turkestan.

“The document called for speeding up assimilationist policies such as moving more Chinese into East Turkistan by giving them Uyghurs’ land and providing them with better jobs while repressing the Uyghurs on all fronts, be it employment, family planning, and so on,” said Mehmet Tohti, a Uyghur political activist in Canada.

“The basic goal of Chinese regime was to gain upper hand in East Turkistan politically, economically, and in number of populations,” he said.

'An unforgettable tragedy'

Behtiyar Shemshidin, who was a police officer during the Ghulja Massacre but later resigned and left Xinjiang, told the WUC and other rights groups that Chinese authorities opened fire on unarmed protesters.

A Uyghur rights activist now in Canada, Behtiyar said the protesters were arrested and tortured. Many detainees, including the demonstration’s leader, Abduhelil Abdulmejid, were tortured to death in prison, Behtiyar said. The violence continued for weeks, he said.

Zubayra Shamseden, the Chinese outreach coordinator at the Uyghur Human Rights Project, a documentation and advocacy group based in Washington, D.C., said her two younger brothers and a cousin were among those who were arbitrarily arrested in the crackdown.

One brother, Abdurazaq Shemsidin, was arrested in Ghulja in 1998 and sentenced to life in prison for “political crimes.” He remains incarcerated in Urumqi’s No. 1 Prison.

The other brother, Sedirdin Shemsidin, was assassinated in Kazakhstan in June 1998. Zubayra Shamseden’s cousin, Hammet Muhammad, was killed by Chinese armed forces in a clash in Ghulja a little over a year after the massacre.

“The Feb. 5 Ghulja Massacre is an unforgettable tragedy that befell not only my family but the entire Uyghur people,” Zubayra said.

Large-scale ‘clean-up’ operation

In the aftermath of the crackdown, an article titled “Let's uncover the terrorist mask of East Turkistan terrorists” published by China’s official Xinhua news agency called the demonstrators, “insurgents.”

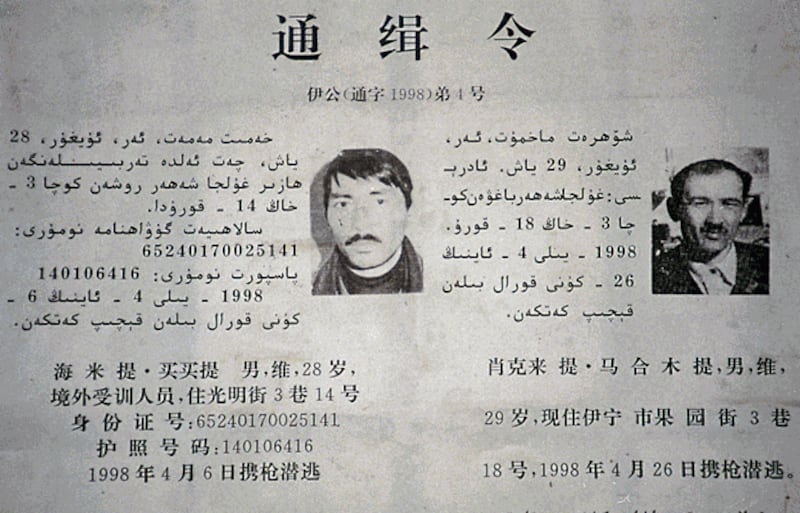

Following the incident, the Chinese government used the protest as a pretext to carry out a year-long large-scale “clean-up operation” throughout Xinjiang under the guise of tracking down suspects, Uyghur sources said.

When the Chinese government began detaining Uyghurs in its networks of internment camps in 2017, former prisoners tied to the Ghulja protest were picked up and sentenced yet again.

The world began to learn of what happened at Ghulja when a video of the protest and crackdown was smuggled out of China and aired in the United Kingdom in 1997. But there were few consequences for China.

In April 1999, a report from London-based Amnesty International said thousands of Uyghurs may have been killed in the incident without reason. Amnesty’s account was based in part on witness testimonies, said T. Kumar, former advocacy director for Asia and the Pacific at Amnesty International in Washington D.C.

“At that time, I would say that the lack of information is one of the reasons our report was helpful to bring the issue to the forefront,” he said.

But, Kumar added, there was little external outcry.

“That was the sad part because but even the U.N. and the international community did not make any noise at that time,” he said. “If that would have happened — if the international community, the U.S., and others would have made a serious attempt to raise the massacre at that time and try to call for justice — the Chinese would have been extremely nervous about continuing the practice of persecution, and now to the extent of imprisoning or detaining around 2 million people.”

Awareness of rights violations

Uyghur activist organizations remain steadfast in calling on the international community to hold China accountable for the massacre.

“This year the commemoration coincides with Beijing Winter Olympic Games, so we have raised an awareness of the Ghulja Massacre along with our other activities on the international stage,” said Gheyur Qurban, a WUC spokesman in Germany.

“The incident is not only important in the recent history in East Turkistan, but also important internationally to raise awareness of Uyghur rights violations perpetrated by the Chinese regime.”

In the generation since the massacre, China’s economic and political strength has significantly grown. Its leaders believe they can get away with extensive abuses against the Uyghurs, Kumar said.

“Twenty-five years ago, they were not as powerful as today, so the challenges are greater for everyone who cares about human rights and the plight of Uyghurs,” he said.

The U.S., U.N., and the legislatures of some democratic governments have declared that China’s rights violations in Xinjiang amount to genocide and crimes against humanity — a charge that Beijing vehemently denies.

Translated by RFA’s Uyghur Service. Written in English by Roseanne Gerin.