China’s far-western region of Xinjiang — called East Turkestan by Uyghurs — is a essentially a colony that China has occupied for the past 70 years, but before that there has not been any continuous Chinese rule there going back 2,000 years – despite Chinese claims, according to Michael van Walt, an international lawyer who has studied the region extensively.

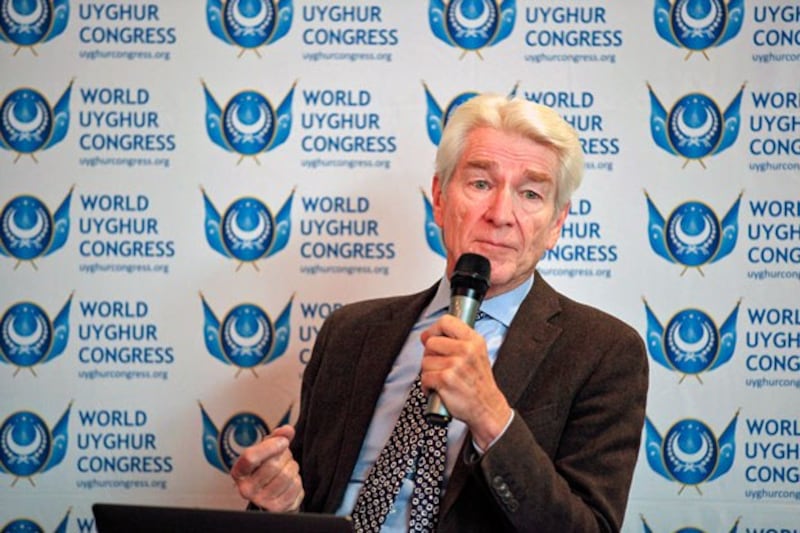

Van Walt, who has specialized in inner Asia and East Asian relations for the past 15 years and works to resolve conflicts in different parts of the world, presented his findings at 20 th anniversary commemoration of the World Uyghur Congress in Munich, Germany, on May 3-6.

In an interview with RFA Uyghur Director Alim Seytoff, van Walt discussed his research. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

RFA: In your presentation, you said that East Turkestan is a colony of the People’s Republic of China and the Chinese government claims that Xinjiang has been an inseparable part of China since ancient times. How do you interpret this latter claim, based on your research?

Van Walt: It's very clear that there has not been any continuous Chinese rule or authority in Eastern Turkestan over the last 2,000 years. Only during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.) and the Tang Dynasty (618-907) was there some presence. Before the Republic of China was established, Eastern Turkestan was ruled by various khanates, mainly from neighboring parts of Asia, but definitely not Han.

RFA: When we refer to China, it's understood that China has existed for thousands of years, and that there has been one country called China, dynasty after dynasty. Is this understanding correct?

Van Walt: No, it isn't, and this is what is causing a lot of confusion. What the People's Republic of China has done, and the Republic of China before it, was to create this idea. There was this national history of China that was projected back into history for thousands of years, as if China had existed as a political entity, as a state, for thousands of years, which it definitely has not.

There have been a number of Han states, empires and dynasties, but the Han people have been ruled not just by Han states, but by many Inner Asian empires as well.

What we call China today was just part of the Manchu empire of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) and the same with numerous others much earlier. So, the present way in which so-called Chinese history is presented — but also, presented sometimes by Western and other scholars — is misleading in that way. It makes it confusing.

And particularly because we use the words “China” and “Chinese,” which can mean many different things.

Today, the PRC [People’s Republic of China] uses the word “China” in Chinese to actually mean all the people that are within what it claims to be the borders of the PRC, whether they are Han Chinese, Tibetan or Uyghur.

But other people use the word “Chinese” essentially to mean Han Chinese and the Chinese language, and the Chinese script to mean the Mandarin script. So, we’re using that word without being precise about what we mean.

If we are being precise, then really the concept of China as a state was imagined in 1911, discussed in 1911, and created in the beginning of 1912 with the Republic of China.

Before that, there were other states with different names, different structures and different principles of governance, which had very little in common with the Republic of China and the People’s Republic of China.

From a legal perspective, those two things are completely different. You cannot talk about the continuity of a state for 2,000 years. It just doesn’t exist. I’m not denying that there was Chinese culture for 2,000 years or 5,000, whatever it may be. I’m not denying there weren't any Han people. All of this is possible. But not continuous or a continuous stream of Han states.

RFA: Why does the Chinese government make this claim, that Manchuria, southern Mongolia, Tibet and East Turkestan were part of China since ancient times?

Van Walt: I can't think for them, but it would seem that the idea was first developed by the Republic of China precisely because it wanted to claim those Inner Asian territories as part of the Republic of China. It needed to develop a rationale for that, needed to develop an excuse for that that would be acceptable. So, they invented this history.

Today, I think the PRC insists on that history and that historical narrative precisely because it does not want to be seen as a colonial power in Eastern Turkestan, Tibet and in Inner Mongolia.

RFA: So, was the first state called "China" established only in 1912, and before that there were different dynasties and empires under different names that had nothing to do with China as a political entity?

Van Walt: No, and the words zhongguo and zhonghua that are used for the name "China" or for "Chinese" existed before for a long time, but they had a different meaning. They had a meaning of "central state" — the central high culture people radiating wisdom and culture out into civilization.

These were civilizational and spatial concepts, not names of states or of a country. Those words were used, and they were transformed to become a label, as a name. Then they were paired to be equivalent to the word “China” in English or “Chine” in French — the Western concept of China, which Europeans had already for a long time mistakenly imagined to be this continuous China, this imaginary country. By pairing the two, it’s made it very difficult, especially for Westerners and Europeans to conceive of the notion that there was not this continuous China because it already existed in our imagination.

RFA: Are Beijing’s claims akin to, hypothetically speaking, Italy claiming that territories occupied by the Roman Empire were part of the country today? Is China’s rationale similar to this?

Van Walt: It is a similar rationale, but there's a distinction. If they really were to do that, they would claim what the Romans had conquered and what they themselves had conquered in the past. What the PRC claims is what the Mongols and Manchus conquered, not what the Han conquered. So, an illogical thing to do.

It’s quite aside from the fact that today in the modern world you cannot claim territory on the basis of some historical claim from 1,000 years ago, 500 years ago or even 100 years ago, which China does. But you certainly can’t claim it on the basis of what another empire did that happened to conquer you.

But the PRC has been able to convince many that whoever ruled what I call the Han homeland — the Han people and their territory — somehow became Chinese or Han. This notion that the Mongols and Manchus were actually Chinese is absurd.

The fact that today the PRC calls Genghis Khan a great son of China is absurd. Genghis Khan is the one who ordered the conquest of China, not as a son of China, but as a son of the Mongols.

RFA: Is China technically exercising colonial rule in the Uyghur homeland by plundering natural resources and by settling Han Chinese into the territories? Is this part of the reason why China is committing genocide against the Uyghurs?

Van Walt: Yes, it is. It is afraid of losing control over Eastern Turkestan and is trying to suppress Uyghurs and others in Eastern Turkestan. It's a way of trying to maintain control. Xi Jinping and his government in particular are bent on absolute control. That is the most important policy objective, so everything is driven by that. And if it means putting millions of people in internment camps, eradicating the cultures of the Uyghurs, Tibetans and Mongolians, and to have absolute control over these territories, then so be it. That is their objective.

As for wanting to control all the territories of the former Qing Empire, they have not finished their objective yet. They still need to achieve that. They will want to control Taiwan, the South China Sea, northern India, and probably parts of today’s Russia, including Tuva and Boryatia, because at some point some Mongol or Manchu ruler ruled some of those areas.

And if we were to go into the absurd, let’s remember that the Mongols ruled most of the Eurasian continent all the way to Hungary, the Middle East and India. We wouldn't really want to see China claim everything that the great son of China, Genghis Khan, achieved.

Edited by Roseanne Gerin and Malcolm Foster.