When an armed police officer directed Uyghur surgeon Enver Tohti to remove organs from a not-quite-dead prisoner on an execution ground outside Urumqi, his first reaction was overwhelming relief: "I thought they were going to execute me," he recalled.

It was 1995 and Tohti was working as an oncological surgeon at the Railway Central Hospital in the northwestern city of Urumqi. He had been pressed into service at the last minute by his chief of surgery, who told him to assemble a surgical team and prepare for "something wild" the next morning.

When the driver turned onto a mountain road that led to the local execution ground, Tohti became "really, really scared" that he would be the target, as the only ethnic minority present. Instead, his team was directed to a man at the end of a row of executed prisoners and told to remove both kidneys and his liver.

Thirty years on, China continues to be plagued by allegations of forced organ harvesting and trafficking, despite banning the use of transplants from executed prisoners. The U.S. Congress is considering a bill that would lead to sanctions on individuals and entities that are proven to be involved.

As an activist and whistleblower, Tohti testified before a U.S. government panel in 2022 about his experiences as a doctor in Xinjiang.

His revelations about organ harvesting as well as high cancer rates in Xinjiang linked to China’s nuclear testing program forced him to flee in 1998 – first to Turkey, and then to London, where he lives today.

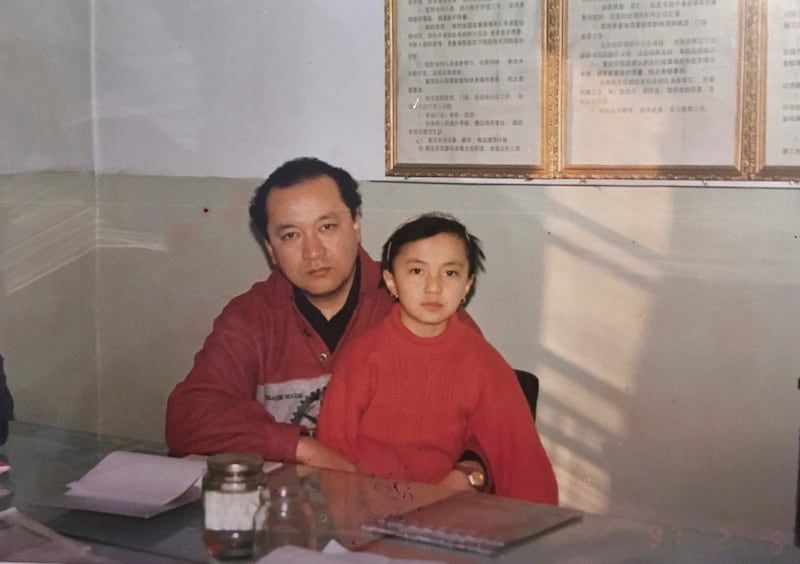

Now in his 60s, Tohti is a serious man, though at times he displays flashes of dark humor. He is a natural talker, offering up stories from his past with a candidness and detail that add credibility to his claims, which have also been independently verified.

Though he has reached a place of self-acceptance over his own traumas, there is a pessimism to his outlook as little seems to have changed and, he believes, the system of abuse he left decades ago continues to operate today.

An unsavory practice

In the past, organ harvesting from prisoners facing execution had been legally permissible in China after a 1984 law allowed the practice in limited circumstances.

Prisoners quietly became the most common sources for transplant over the next decades as organ donation was rare. By 2011, some 65% of transplants in China used organs from deceased donors, more than 90% of whom were executed prisoners, according to a paper in the U.K. medical journal The Lancet by the then-Chinese Vice Health Minister Huang Jiefu.

The practice was condemned by international medical and human rights organizations and was banned in 2015 following an outcry as evidence emerged of forced harvests, and corruption. Critics alleged that prisoners of conscience were executed for political reasons.

In recent years, the Chinese government has repeatedly vowed to crack down on organ trafficking, with the latest law due to go into effect on May 1. But these efforts have been seen by some as a tacit admission that the medical transplant system in China – which is overseen by the state – still operates on harvested organs.

Rights activists say there is evidence that the government continues to be complicit. The ongoing mass internment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, along with a project to collect vast DNA samples from the population, offer opportunities to target the group for organ harvesting, human rights advocates fear.

Ethan Gutmann, a research fellow at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, has testified about first-hand accounts of interned Uyghurs in their mid-20s to early 30s being given mysterious medical exams. Certain people are then tagged and subsequently vanish from the camps, he was told by a doctor who worked at one.

These instances, along with the construction of infrastructures like crematoriums and special transport lanes near hospitals and at airports in Xinjiang, point to organ harvesting, he said.

However, individual cases are difficult to verify and concrete evidence is hard to come by.

RFA contacted the Chinese Embassy in Washington for their comment on Tohti’s story, Gutmann’s testimony, as well as to request an update on any law enforcement activity.

Spokesman Liu Pengyu responded by email: “The relevant claims are pure lies and malicious smears against China.”

Disturbing findings

Tohti told RFA that he finds Gutmann’s conclusions and the suspicion that organ harvesting continues in China today to be credible (he has known Gutmann for years) but that Uyghurs aren’t the only victims.

“Anyone is a target for organ harvesting under the rule of the Chinese Communist Party,” he said.

Tohti says he first became aware of the issue five years before his trip to the execution ground, when a Uyghur man brought along his teenage son who had recently returned home after going missing. The man feared his son's organs may have been taken during his absence, citing similar cases among returned missing Uyghur children in his rural hometown.

There were no surgical scars on the boy's body, and Tohti was able to reassure him. But the man went home and told his friends that there was a Uyghur doctor at the Railway Central Hospital who would check their kids, and dozens of them showed up during his six-month rotation at the outpatient clinic.

"I found scars on three of them," Tohti said. "The ultrasound confirmed that they had one kidney missing."

He first spoke about his involvement at a public event in London – at a meeting of the Henry Jackson Society, a conservative think-tank, in 2009, where Gutmann was presenting his research on organ harvesting.

"I wasn't prepared to confess, but my hand was raised up,” Tohti recalled. “God raised my hand.

"That day I ... feared they [those gathered] wouldn't accept me," he said.

Since that first public confession, he has gone on to retell the story more confidently, as an activist. He has repeated it to newspapers, online video channels, to the U.S. Congress and to human rights groups.

His fears of judgment for disclosing the experience weren't entirely unfounded, though.

He has been unable to carry on practicing medicine in London due to failing stringent language requirements by the British National Health Service, instead finding jobs as a driver. After The Mirror, a U.K. newspaper, ran a story about his experience in 2020, he found himself under review by London's traffic authority as a result of a "notification of an adverse nature," according to a Dec. 30, 2020, letter to Tohti. He was driving for Uber at the time.

A spokesperson for the agency declined to comment on the reasons for the investigation, but disclosed that it concluded he was a whistleblower.

"During the period of the investigation he was able to continue driving and at the conclusion of the process it was decided no further action should be taken," the spokesperson said. By then, Tohti was working as a backup driver for a friend with a truck.

Haunted but numbed

For Tohti, the impact of the horrors of the organ harvesting system was somewhat blunted by a childhood that coincided with the political brutality of China's Cultural Revolution (1966-76).

"I think I basically saw at least a couple of dead bodies a year," he said, recalling running wild with a gang of other kids around the railroad tracks near his home.

"These were people who had been targeted by struggle sessions, and then killed themselves," he said. "Sometimes they would jump off buildings, or they would lie across the rails so that their necks would be sliced off by a train.

"We were pretty inured to stuff like that, to horror stories of the kind that you couldn't broadcast on TV," he said. "For us, it was normal."

Before testifying about organ harvesting, Tohti was already a known whistleblower, having played a major role in a documentary by U.K. broadcaster Channel 4 about the high incidence of cancer in Xinjiang, which is widely believed to be linked to China's nuclear weapons testing near Lop Nor, a now-dried lake in southeastern Xinjiang.

He still remembers a racist dig from his boss in 1995 that needled him into researching cancer rates among Uyghurs that eventually led him to his conclusions.

His boss had taunted him with the claim that Han Chinese must be superior to Uyghurs, because there were fewer Han cancer patients in their ward. Tohti noticed that the proportion of Uyghur patients was higher than expected for predicted cancer rates, given that only around 5,000 out of the 150,000 or community members who used the hospital were Uyghurs.

"[Later] the director saw what I was doing, and told me not to touch it," Tohti said. "He said it will be very bad for you."

But Tohti carried on researching the figures in secret, sneaking off to the medical records library during his free time, and digging up the notes of cancer patients without his boss's knowledge.

What he found was a disproportionately high number of malignant lymphomas, leukemia cases, lung cancers and birth defects among Uyghur railway employees and their families who had lived in Xinjiang throughout the 1964-1996 nuclear test program, compared with their Han Chinese counterparts, who had only spent part of their lives in the region.

"They said it wasn't harmful to humans," Tohti remembers of the open secret that was the nuclear test program in Xinjiang.

“I remember making a silly joke at the time – if the tests aren't harmful to humans, then what's the point of them? Aren't they supposed to kill people?"

But, he added somberly: "If these cancers are all linked to radiation, then where was the radiation coming from?"

By 1998, Tohti was in Istanbul, studying a foreign language in order to qualify for a promotion further up the medical hierarchy. While there, he was contacted by Channel 4, and eventually traveled back to Xinjiang with two journalists disguised as tourists and personal friends.

They dove back into local medical records, concluding that cancer rates were as much as 35% higher in Xinjiang than the national average. Uyghurs were disproportionately affected because those seeking treatment at the Urumqi Railway Central Hospital had mostly grown up in the region, while the Han Chinese were more likely to have been posted there as adults, and not been exposed to so much radiation, according to Tohti’s data.

Tohti then fled back to Turkey to avoid the political fallout from the airing of the film, and later applied for political asylum in the United Kingdom, as Turkey was weighing an extradition agreement with China.

He hasn't been back since, and has been cut off from his friends and family there, eventually remarrying and raising more children in the ultra-hip London borough of Shoreditch.

For now, Tohti has decided to dedicate himself full time to organizing on behalf of Xinjiang and the Uyghur people. In 1990, he had quietly converted to Christianity as a young surgical resident after witnessing people praying with Bibles at the bedside of dying cancer patients who refused pain medication at the end of their lives, leaving him with a physical reaction he described as "electrifying" and which he now attributes to God. Both patients left him their Bibles.

Today, his activism increasingly includes Christian missionary work.

Despite offering his testimony, he is skeptical about whether the U.S. Stop Forced Organ Harvesting bill will solve the problem.

“It won’t have much effect, because Chinese officials are adept at evading U.S. sanctions,” he said, adding wryly that such measures can at least offer a talking point for journalists and politicians.

He is fairly sure that agents of the Chinese government continue to watch him and assumes that his computer has long since been hacked. He wonders to this day whether a freak car accident in the Alps on Christmas Day 2016 was the result of sabotage by unknown actors.

Yet he has reached an uneasy peace with himself about his experiences.

"The society I was in before was a barbaric society,” he said. “I was born there.”

"So I try to teach myself … and then try to just bring the truth to light."