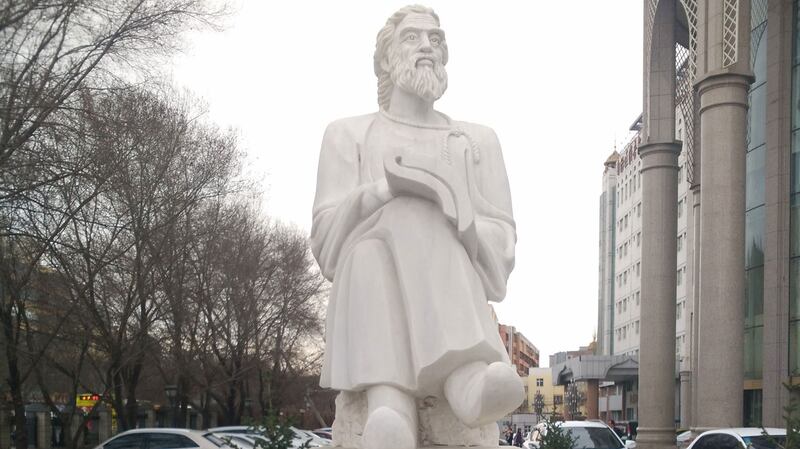

Authorities in northwest China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) have removed the statue Mahmud Kashgary, one of the Turkic world’s most important scholars, according to satellite imagery.

Using satellite imagery, RFA’s Uyghur Service was able to determine that Kashgary’s statue was removed sometime after Nov. 28, 2019.

The seven-meter statue of the Uyghur academic, who compiled the "Grand Turkish Dictionary" in the 11th century, had stood on the grounds of a mazar, or shrine, dedicated to him outside of Opal township, in Kashgar (in Chinese, Kashi) prefecture's Kona Sheher (Shufu) county since the mid-1990s.

From the early 1980s into recent years, numerous scholars in China have researched and published about Kashgary and his work, and numerous national and international scientific seminars on the topic of his work have been held in Urumqi and Beijing.

His resting place was renovated with approval and funding from the XUAR People's Government in the early 1980s. The mazarhas since been designated as a key protected cultural site in China, and has been a key tourist site for both domestic and international tourists to the region.

However, in a Chinese-language article published in the Xinjiang University Journal in 2019, titled “Doubts and Reflections on the Author of the Compendium of the Turkic Languages and His Tomb,” author Gao Bo, an ethnic Han professor affiliated with the Center for Northwestern Minority Studies of Xinjiang University, cast doubt on many of the historical claims about Kashgary.

In the article, Gao challenges historical narratives about Kashgary’s life, claiming that there is no credible evidence to support the conclusion that he was Uyghur or that Opal was his hometown. The statue appears to have disappeared just months after the article’s publication.

A well-known historical figure in the cultural history of the Uyghurs, as well as of all the Turkic peoples, Kashgary's Compendium is still referenced and studied by scholars around the world today, and holds an important place in Turkic cultural history. His mazar has served as an important cultural and holy site for Uyghurs from all walks of life, and was even visited by Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu in 2010.

Uyghur ‘eliticide’

Alimjan Inayet, a professor at the Turkish World Studies Center at Ege University in Izmir, Turkey, called the statue’s removal “a severe blow” to Uyghurs and all Turkic peoples.

“They understand Mahmut Kashgary to be the grandfather of Turkology and folklore. In this sense, Mahmut Kashgary is the glory of the Turkic world,” he told RFA in an interview.

“The demolition of the statue of Mahmut Kashgary by the Chinese government is a declaration of war on the Turkic world, on all the Turkic peoples,” he added, calling on a strong response to Beijing from the Turkic diaspora.

Inayet noted that the Chinese government has “consistently attacked Uyghur culture and attempted to sever ties between the Uyghur people and their ancestors” since establishing the XUAR under Beijing’s rule in 1949.

“The elimination of our historians and religious scholars, the detention of hundreds of famous intellectuals in camps and prisons, as well as the demolition of thousands of our historic structures, shrines and statues of famous individuals, one after the other, are clear evidence of the Chinese government’s great conspiracy against the Uyghur people,” he said.

RFA also spoke with Henryk Szadziewski, director of research at the Washington-based Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP) and a former resident of Kashgar, who compared Beijing's targeting of Uyghur cultural touchpoints to the repression of other ethnic groups by fascist regimes of the 20th century.

“It was an important site for Uyghurs to go to, not only to learn about their history and culture, but also as a place to go recreate,” Szadziewski said, noting that he had regularly gone to the site with friends and students when he taught in the area.

“The broader implication here is that we have seen a Chinese government assault on Uyghur intellectuals, since 2017 in particular—many of them interned, disappeared, or in prison,” he added.

“We know that one of the stages of genocide is to eliminate intellectual life, but also the people themselves in terms of an ‘eliticide,’ so Uyghur culture … the people who are writing about Uyghurs, and passing on knowledge about Uyghurs are removed, and the only context provided is a Chinese history, and the Chinese culture.”

According to Szadziewski, the statues' removal is simply "part of that process," noting that they come after extensive documentation of the demolition of mosques, mazars, and cemeteries across the XUAR.

“The destruction of the statues follows in the wake of that development, because what we're seeing here is just the erasure of the tangible elements of Uyghur culture and history,” he said.

Szadziewski said such measures amount to a “clearing of the land of Uyghurs and their links to it” to create a new environment in which ethnic Han settlers can take advantage of economic opportunities that marginalize the Uyghurs.

“Any government that has engaged in genocidal processes from the past—Soviet or Nazi or any other regime engaged in the removal or wholesale removal of a people and their culture—has begun with the assault and attacks on intellectual life,” he said.

“Not just the people, but also their cultural production and historical production, too. So, I feel like we're seeing these signs now that are facing the Uyghurs.”

Other statues

By combing through additional satellite imagery, RFA was able to locate at least two other statues of Uyghur icons that had been removed in recent years, as part of what observers say is an ongoing campaign to eradicate the ethnic group’s culture.

One of the statues depicted Ghazibay, a pioneer of Uyghur medicinal science, which was taken down from in front of the XUAR Hospital of Uyghur Medicine in the regional capital Urumqi.

Ghazibay, who lived in present-day Hotan (Hetian) between 460 and 375 B.C., was the author of a famous medical treatise—the modern Uyghur-language title of which translates as “Ghazibay’s Encyclopedia of Herbal Medicines.” His research is believed to have drawn disciples of Plato from Greece to the Tarim Basin.

RFA received confirmation from a nurse at the hospital that the statue of Ghazibay was removed from the site and used satellite imagery to determine that the act occurred sometime between Oct. 26, 2017 and March 9, 2018. The timing of the removal coincides with the launch of a campaign of extralegal incarceration that has seen up to 1.8 million Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities detained in a vast network of internment camps in the XUAR since early 2017.

More recently timestamped videos and other evidence suggest that that the site where the statue once stood now serves as a dedicated space for flag-raising ceremonies, the singing of “red”—or patriotic—songs, and other such forms of compulsory Communist Party-led political education.

Also removed was a statue of Hussayn Khan Akbar Tejelli—a famous Uyghur poet and medical scholar who lived in the late 19thand early 20th centuries—from the grounds of the Kargilik (Yecheng) County Hospital of Uyghur Medicine in Kashgar prefecture. One of the last satellite images to show the statue in place dates to July 8, 2017.

Born in 1856 in the village of Aybagh, in Kargilik’s Zonglang township, Tejelli and his father, physician Shah Hezret, went on the holy Islamic hajj pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia, where he received his primary education. Afterward, he studied in India, Iran, and Afghanistan, excelling in a range of disciplines, including linguistics, history, logic, nature, astronomy, chemistry, medicine, and mathematics.

Tejelli, much like Ghazibay, was considered one of the progenitors of modern Uyghur medicine—a tradition that stretches back for more than 2,000 years. His statue was erected in 2016 and reported on by state media at the time, calling him a “great Uyghur scholar and poet.”

Ongoing campaign

Last year, UHRP was one of the first organizations to publish a report on a wave of Chinese government-led demolitions of mosques and mazars in the XUAR. Earlier this year, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) released another major report on the topic, estimating that 35 percent of the region's mosques have been destroyed since 2016.

The two reports put the number of demolished mosques, mazars, and other significant cultural-religious sites in the region at 15,000 or more.

International experts and media outlets have long been reporting that the Chinese government is waging a “cultural genocide” against the Uyghurs. In recent months, the governments of several Western democracies have also begun inquiries into whether the crisis warrants designation as genocide or have proposed resolutions to recognize the crisis as such.

Reported by Bahram Sintash for RFA’s Uyghur Service. Translated by the Uyghur Service. Written in English by Joshua Lipes.