In July 2016, when Pham Nhat Vuong, chairman of Vingroup and the richest man in Vietnam, was asked if he would recommend investing in Ukraine, his reply was candid: “To be honest, I don’t think you should invest in Ukraine.”

In the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of its neighbor last week, his comments seem prescient. Vuong, who went to Ukraine 30 years ago as a student and made his first dollars in the city of Kharkiv, gave his reason: “They [Ukraine] are stuck in a conundrum that sees no solution in the near future unless they go with Russia. If they decided to go with the European Union, Russia would never leave them alone.”

“But they can’t lean towards Russia as long as this regime is still in power. In short, the situation in Ukraine at the moment is very complicated.”

Vietnam’s so-called “red capitalists” seemed highly aware of the precariousness in Ukraine yet officialdom, including senior diplomats, were caught off-guard when President Vladimir Putin ordered the full-scale offensive on Ukraine on Feb. 24 – an action that has caused bloodshed, mass displacement and international outrage.

It’s also placed countries in Southeast Asia in a diplomatic bind. Individual governments, and the regional bloc, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN, face a mounting challenge in balancing relations among the world’s superpowers.

While Southeast Asia’s economic ties with Russia are comparatively small, how countries respond diplomatically to the Russian aggression could also have implications for their relations with China, which has steered clear of direct criticism of Moscow. Russia is also an important source of military hardware for a number of countries in the region.

There already been stark differences in how the 10 members of ASEAN have responded to the Russian invasion of its neighbor.

“With Singapore’s decision to impose economic sanctions against Russia and Indonesia’s condemnation of Russia’s military assaults in Ukraine, ASEAN may now find it difficult to come up with a clear and united framework when dealing with Russia,” said Stephen Nagy, senior associate professor at the International Christian University in Tokyo.

Vietnam’s dilemma

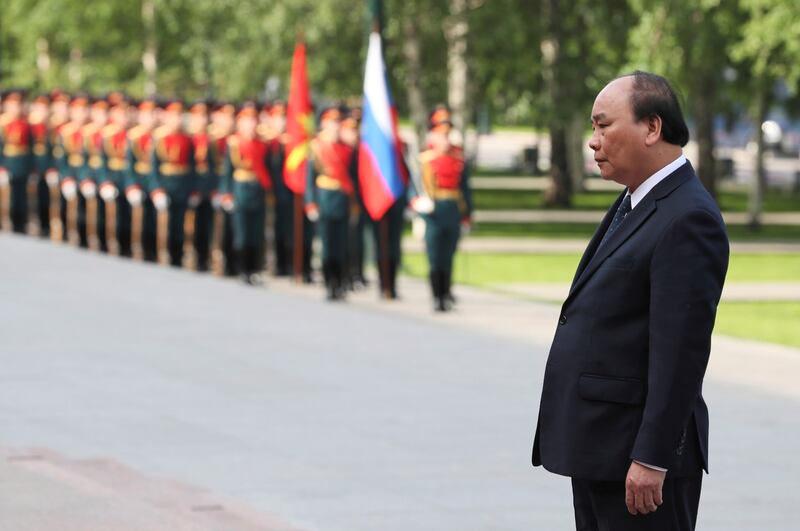

In ASEAN, Vietnam has the strongest historic ties with Russia and perhaps the most at stake in how the Ukraine conflict plays out.

A Vietnamese government senior analyst said: “We didn’t believe it when there were clear warnings in Western media and in our talks with international partners about an imminent attack.”

“Perhaps there was some denialism on our part, because this conflict would have put us in a very difficult position,” said the analyst, who wished to stay anonymous as he was not authorized to speak to foreign media.

Vietnam joined other Southeast Asian countries in issuing a statement on the situation in Ukraine that not only did not condemn Russia's aggression but also did not even mention Russia.

At the United Nations General Assembly special session on Ukraine on Tuesday, Vietnamese Ambassador Dang Hoang Giang stuck to well-rehearsed calls for restraint, dialogue, and long-term solutions to differences – although some interpreted his reference to how “wars and conflicts often stem from outdated doctrines” as implicit criticism of Putin.

The Vietnamese analyst, however, noted: “We can’t afford to offend Russia as there will be post-war dilemmas to consider.”

'Of Western making'

Among ASEAN countries, Singapore and Indonesia have separately condemned the Russian invasion – and on Monday the Philippines joined them in expressing "explicit condemnation of the invasion of Ukraine" – a change of tack after the country's Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana had said that "it's none of our business to meddle in whatever they're doing in Europe."

Others in Southeast Asia view the Ukraine conflict through a similar lens.

Kasit Piromya, Thailand’s former foreign minister and former ambassador to Moscow, said: “ASEAN should not be involved. It was European affairs and of Western making.”

“All could have been prevented from the beginning if the U.S. did not keep on pushing NATO towards the Russian borders and took into consideration the Russian call for its security concern,” he told RFA.

“Now Putin is being pushed into a corner and his eventual and final reaction will be unpredictable. The Russian nuclear forces being put on the alert cannot be taken lightly.”

“Biden and Putin have to speak to one another as soon as possible,” Kasit said.

Cambodia, the current of ASEAN, says it is staying neutral and urging a negotiated settlement. But on Wednesday, Prime Minister Hun Sen also said he opposes Europe sending weapons to Ukraine.

“Sending weapons will worsen the war,” he said.

ASEAN reality

One of the main arguments that the U.S. and its allies use to rally support from other countries in condemning Russia is that they should oppose great powers’ unilateral actions to invade or coerce relatively smaller states.

Singapore’s Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan said in his speech Monday when announcing sanctions against Russia: “Unless we, as a country, stand up for principles that are the very foundation for the independence and sovereignty of smaller nations, our own right to exist and prosper as a nation may similarly be called into question.”

Nagy said that reflected Singapore’s lack of strong and deep economic relations with China, and its need for “to work with like-minded countries to have a strong and coherent approach to secure the rules-based order.”

But for many smaller countries in Southeast Asia, the response to the Ukraine crisis may boil down to their own calculations of the regional reality where another super power – China – is looming large.

Just a month ago, on the sidelines of the Beijing Winter Olympics, China and Russia issued a joint statement confirming the mutual support and the deepening of diplomatic ties between them.

“The response to the ongoing Ukrainian conflict depends on the economic relationship that each Southeast Asian country has, as well as how they view China's reaction if Southeast Asian countries take a strong stance vis-a-vis Russia,” said Nagy.

“Many in Southeast Asia may not want to directly criticize Russia for fear that it may anger or promote China to be more aggressive towards its island positions in Southeast Asia,” he added.

Several ASEAN countries, including Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam, have territorial disputes of various extents with China in the South China Sea.

Future of relationship

Russia and Ukraine both have weak economic relations with countries in ASEAN.

Russia only accounted for 0.53 percent of ASEAN's overall goods trade by value in 2020, and Ukraine only 0.1 percent, according to ASEANstats, the bloc's data portal. The two countries' direct investment into ASEAN is even smaller.

The real value of Russia's relations with some of ASEAN countries lies in the defense and security domain. Russia is the biggest arms supplier in Southeast Asia, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

But Nagy said that the future of Russia-ASEAN relations depends largely on “the success or failure of Putin and his invasion of Ukraine.”

If the West is successful in pressuring the Putin regime to step back through economic statecraft and a much more consolidated and coherent approach, “it may put Russia in a weaker position moving forward,” he said.

Some analysts believe that with Putin still in the presidency, ASEAN-Russia relationship will turn sour.

“In the days to come, ASEAN, as a bloc in United Nations, would have to reject Russia outright,” said Phar Kim Beng, founder of Strategic Pan Indo-Pacific Arena (SPIPA), a think tank, adding: “Otherwise, many Europeans, Americans, Japanese, and South Koreans would not find ASEAN a trustworthy place for foreign direct investment and tourism.”

“Any countries that are stillsupportive of Russia, would not only have their reputation tarnished, but their citizens' lives trapped in Ukraine in serious peril,” Phar said.

For those ASEAN countries which choose to navigate between superpowers, the balancing act after the latest developments in Ukraine will be even more difficult to maintain, said Huynh Tam Sang, a lecturer at Ho Chi Minh City University of Social Sciences and Humanities in Vietnam.

“The Russia-ASEAN relationship will be put to the test following Russian President Vladimir Putin’s potential attendance at ASEAN-related summits scheduled to take place in December this year,” Sang said.