H’Soan Siu said her 14-year-old sister, H’Xuan, called from the airport in late 2018 to tell their family she was leaving for Saudi Arabia to work for a family there. H’Soan never saw her younger sister again.

H’Xuan died after being repeatedly beaten by her employer, who also denied her medical care and food, H’Soan said.

Her case was noted earlier this month in a special statement from the U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights warning of “truly alarming allegations” that companies in Vietnam were recruiting girls as domestic workers and lying about their ages to hide the fact they were children.

“We are seeing traffickers targeting Vietnamese women and girls living in poverty, many of whom are already vulnerable and marginalised,” the U.N. said. “Traffickers operate with impunity.”

H’Xuan’s nightmare began when a woman named Le Thi Toan from VINACO, and international labor export company in Thanh Hoa province, invited her sister to get a passport so she could work overseas, H’Soan told RFA.

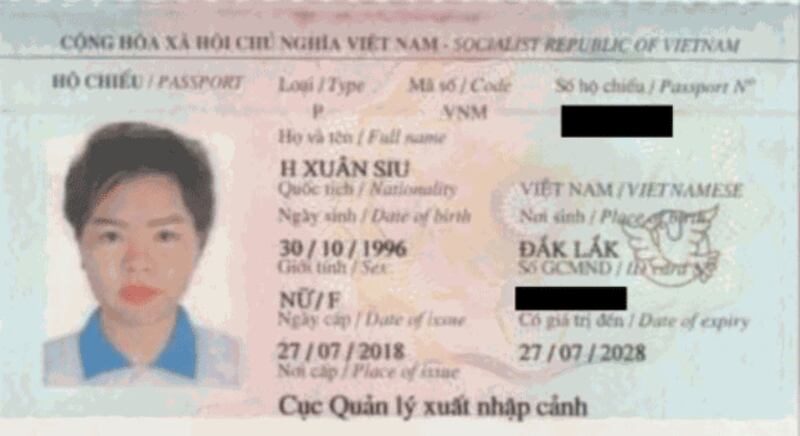

The family only became aware of this when H’Xuan called them from the airport, saying that she was about to leave for Saudi Arabia. She said the passport she was given prior to her flight had a wrong birth year, 1996, instead of 2003.

H’Xuan immediately had misgivings and asked Le Thi Toan to allow her to return home. She was told she could return only if she reimbursed the company the 30 million dong (U.S. $1,324) it had paid for her belongings and accommodation, H’Soan said.

Without money, H’Xuan had no choice but to leave for Saudi Arabia.

In October 2019, H’Xuan called again to say that she was working for an Arab family.

H’Xuan called an intermediary named Ms. Nhung for help but received a scolding instead, according to her sister.

Heart failure

The teenager also contacted Nguyen Quoc Khanh, who was in charge of guest workers affairs at the Vietnamese Embassy in Riyadh, and told him that she could not tolerate the situation it any longer and asked to leave her employer’s home. The agency would not agree to it, however.

“Finally, H’Xuan told us she would try to stay there some more months and return home when flights were available,” H’Soan said.

She never made it home.

H’Soan said the family lost contact with her sister in July, when a representative from VINACO told them that H’Xuan had been hospitalized for heart failure. Four days later, the company notified the family that H’Xuan had died.

Calls by RFA’s Vietnamese Service made to Khanh at the Vietnamese Embassy in Riyadh and to VINACO received no reply.

A 2018 report by the Vietnamese National Committee on Crime Prevention and Control identified about 7,500 victims of human trafficking between 2012 and 2017, more than 90 percent of whom were female and 80 percent of whom came from remote ethnic communities.

Vietnamese who fall prey to human traffickers usually come from impoverished and vulnerable families and communities and lack education or awareness of human trafficking.

H’Xuan was not the only girl who VINACO sent to Saudi Arabia to work.

At least three other young girls were sent to VINACO to Saudi Arabia to work — H’Ngoc Nie, who returned to Vietnam in September 2020, and Siu H’Chiu and R’Ma Nguyet, who remain in Saudi Arabia, said Nguyen Dinh Thang, president of Boat People SOS, an NGO which rescues trafficked Vietnamese.

“VINACO Company often targets Central Highland adolescents who live far away from urban areas as in the case of H’Xuan, who was enticed by Le Thi Toan to visit Thanh Hoa City without her family’s knowledge,” he told RFA.

H’Ngoc Nie, who is now 17 and is a member of the E De ethnic minority group, told RFA that intermediaries from Thanh Hoa City came to her village in E H’Leo district, Dak Lak province, saying that if they worked in Saudi Arabia they could send enough money back to Vietnam to support their families.

No rest

H’Ngoc said she was also given a passport that falsely listed her birth year to make it seem like she was older than she really was. She arrived in Saudi Arabia in October 2018 and was treated like a slave by the family she worked for and only allowed to sleep three or four hours a night.

“I had to work around the clock while they only ate, sat, and did nothing,” she said. “They ate a lot and never let me have a rest.”

Desperate for help, H’Ngoc said she called VINACO’s representative in Riyadh only to be told that she “should be able to do what others could do.”

At first, she was able to send her mother the salary she earned. But after a year, her employer stopped paying her.

A woman who identified herself as Gam from Vietnam’s southern province of Long Xuyen told RFA in September that she went to Saudi Arabia for work in 2019 and now lives at the Sakan Center, an entity under the Saudi Arabian government that provides legal assistance to migrant workers.

Gam arrived in Saudi Arabia in September 2019 and was immediately taken to her employer’s home to work as a domestic aide.

“The master family treated me very poorly and without respect,” Gam said. “I was only allowed to eat left-over food and had only one main meal a day. Sometimes, when I was too hungry, I had to wait until when my masters went out so that I could steal some food and hide it in my room to eat in the evening.”

She was also beaten, but when she reached out to her employment agency for help she was ignored.

Gam said she eventually reported the abuse to local police, who allowed to return to Vietnam. But she was stuck in Saudi Arabia because airports and borders were closed due to the coronavirus pandemic.

“Then my intermediary office ‘sold’ me to another intermediary, and that office sent me to a new family to work,” Gam said. “In total, I have been sold to four different masters.”

The intermediary office kept her wages, and that all of her employers beat her “black and blue” until she decided to escape while the last one was sleeping.

‘Cheated, sold and bought’

As Gam was running along a street, a driver stopped to help her contact police. She ended up in the Sakan Center.

“I had been cheated, sold and bought. I went abroad to work, but it left me empty-handed,” she said.

H’thai Ayun, from Buon Ma Thuot, a province in Vietnam’s Central Highlands, also worked as a domestic helper in Saudi Arabia.

“I had to do everything from A to Z,” she told RFA. “My master did not give me sufficient food. When I got sick, they wouldn’t get me to the clinic unless I paid for it.”

H’thai Ayun also asked the intermediary office to find another employer for her but was told that if she wanted to work for another family, she wouldn’t get credit for the time she had already worked in Saudi Arabia. She would have to sign a new two-year contract.

Unable to return home because there were no flights to Vietnam during the pandemic, she instead sought refuge at the Sakan Center.

“I noticed that all of my fellow Vietnamese women taking shelter at the center had been treated badly and beaten up by their masters,” H’thai said. “They had to escape from their masters’ homes without either salary or belongings. They have nothing with them.”

H’thai and other women at the center made a video demanding that they be allowed to return home.

Three days after the video was posted on social media, Nguyen Quoc Khanh, a diplomat from the Vietnamese Embassy in Riyadh, went to the center to threaten H’thai, telling her that the video contained content against Vietnam. The diplomat said that she was now on a “special” list kept by the embassy.

This September, the embassy told H’thai that she would be given a free air ticket sponsored to return home. But she asked to stay at the Sakan Center because she feared that the Vietnamese government would punish her for the video.

In September, the Sakan Center had provided shelter for 38 Vietnamese female guest workers who were maltreated by their local employers; 29 of the women returned home early that month. The remainder do not know when they will fly back to Vietnam.

Thang of Boat People SOS said many of the women at the facility had fallen prey to human traffickers.

“Almost all of them have completed their two-year contracts but were not allowed to leave their masters’ home as the Vietnamese government said there were no repatriation flights and their companies/intermediary offices did not want to them to end the contract,” Thang said. “The intermediary offices forced them to stay further so that it didn’t have to feed them or compensate them. This is an involuntary factor.”

Thang said files his group compiled on the women were sent to the U.S. Embassy in Saudi Arabia. Eventually the Human Rights Council of Saudi Arabia helped mobilize the police to intervene and free the women.

“We were also referred to international organizations specializing in repatriation, and they provided assistance to the victims that we spoke to,” Trang said. “Then the Human Rights Council of Saudi Arabia also stepped in, and they mobilized the police for intervention and rescue.”

Vietnamese Foreign Affairs spokesperson Le Thi Thu Hang said the country's diplomatic missions monitor agencies and firms that that recruit female workers to ensure good working conditions.

"At the same time, the Ministry stands ready to carry out measures to protect Vietnamese citizens and their legitimate rights and interests as necessary, especially those of women and children," she told a news conference last week.

The spokeswoman said that the Ministry and the Vietnamese Embassy in Saudi Arabia "proactively" dealt with recent abuse reports in the country and had brought nearly 800 Vietnamese citizens back to Vietnam safely.

“Vietnam’s responsible agencies will continue to work with host countries’ responsible agencies to organize more flights to repatriate Vietnamese citizens who wish to return or are in extremely difficult circumstances in accordance with citizens’ desire, the pandemic developments in the world as well as Vietnam’s quarantine capacity,” said Le.

Translated by Anna Vu for RFA’s Vietnamese Service. Written in English by Roseanne Gerin.