Myanmar’s military dictator, Min Aung Hlaing, returned from a five-day trip to China, his first since the February 2021 coup, with promises of further Chinese assistance, in a desperate attempt to shore up his flailing regime and bankrupt economy.

Min Aung Hlaing was invited to attend the 8th Greater Mekong Subregion Forum, and was kept confined to Kunming, the capital of neighboring Yunnan province.

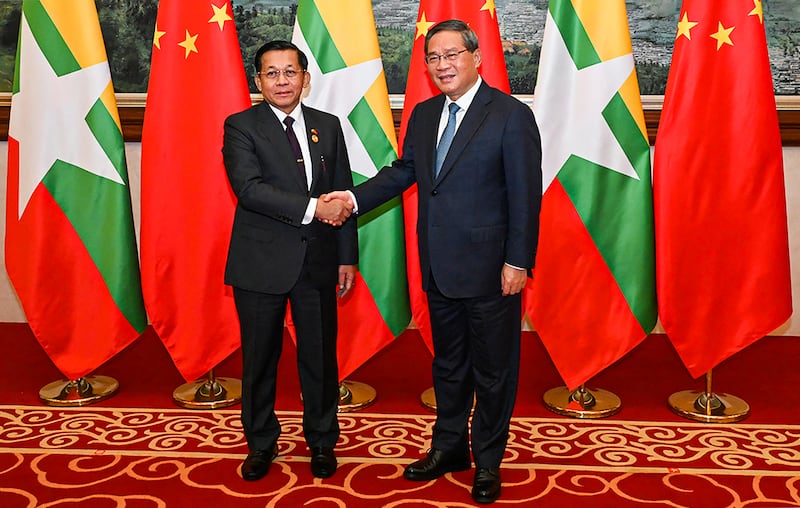

Though he failed to get the legitimizing meeting with Xi Jinping that he had hoped for, he held talks with Prime Minister Li Qiang.

The junta chief had one overriding priority: securing additional Chinese military assistance.

The junta leader pledged that he was ready to sit down and talk peace with the opposition, but only “if they genuinely want peace” – i.e. stop fighting.

There were other matters on his agenda.

Min Aung Hlaing met with the prime ministers of Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. It was the first time since the coup that the State Administrative Council – as the junta is formally known – enjoyed such diplomatic legitimization.

The junta chief also met with Chinese businessmen and state-owned enterprises, promising an array of tax holidays in return for investments in energy, infrastructure or electric vehicle projects.

So desperate for investment, Min Aung Hlaing promised that all projects could be funded with yuan, rather than U.S. dollars. Despite traveling to China with a large contingent of military-backed businessmen, he returned home with no firm commitments of investment.

China continues to push for a ceasefire and has backed progress towards national elections.

At the same time, Beijing has stepped up support for the military, which may have been the justification for the Oct. 18 grenade attack at their consulate in Mandalay.

Anti-Chinese sentiment has never been higher among the opposition and citizenry.

Border trade, railway construction

Li Qiang had two inter-connected priorities in his meeting with Min Aung Hlaing.

The first was the reopening of border trade, which China had shut to pressure the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and the Three Brotherhood Alliance, who control almost all border crossings, to stop their offensive.

The second was the start of construction of the rail line and highway from the Chinese border town of Ruili to the Chinese concession in Kyaukphyu, where Chinese firms are constructing a special economic zone and deep-water intermodal port.

In the face of potential tensions with the United States, the Andaman Sea port is a strategic priority for Beijing that fears the U.S. ability to block the Strait of Malacca.

The KIA and the Three Brotherhood Alliance continue to defy China, despite the economic damage to the local population, which is highly dependent on border trade.

As of now only one of five official border posts, Mongla, is open. China has not restored electricity and internet service to many of the border towns as punishment.

Under Chinese pressure, the Myanmar National Defense Alliance Army (MNDAA), had to publicly distance themselves from the National Unity Government (NUG), the shadow opposition government.

And yet they continue to defy Beijing, both continuing their military operations and coordination with the NUG.

Since July, the KIA has captured 12 more towns and has started to establish administrative control over the entire border region, having taken the last border crossing after defeating a border guards force loyal to the junta in Chipwi.

Beyond the border region, the KIA continues operations around the jade mining town of Hpakant. It has also captured six towns in Sagaing and Northern Shan state.

Counter-offensive

The military has stepped up its counter-offensive in Northern Shan state. Communities have experienced intensified aerial bombing while there has been a growing ground offensive in Nawnghkio township, which is under the control of the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA).

Nawnghkio puts the TNLA in the artillery range of the symbolically important city of Pyin Oo Lwin, the home of the elite Defense Service Academy, where all officers are educated.

There are reports of the military regime building up their defenses around the city, including new trenches and increased checkpoints.

Despite the increased fighting, the military has had a rough time against well-dug-in MNDAA and TNLA forces.

The military has put more effort into retaking lost territory around Loikkaw in Kayah state, taking advantage of diminished stockpiles of ammunition among the opposition.

In western Myanmar, the Arakan Army continues their assault on Ann township, the headquarters of the Western Military Region, which began on Sept. 26.

While the town has not fallen, the military has had to mobilize a lot of reinforcements. In the process they lost one of their few Mi17 heavy lift helicopters to ground fire.

Chin resistance forces in neighboring Chin state have reportedly captured some retreating military forces.

The Arakan Army has not seized Kyaukphyu but holds all the surrounding territory. The force currently controls 10 of Rakhine state’s 17 townships.

The junta military is now stockpiling men and equipment in Gwa, the southernmost city in Rakhine, for a counter-offensive north along the coastal highway to retake lost territory and take off pressure from their beleaguered forces in Ann.

RELATED STORIES

Perhaps it would be better if Myanmar’s civil war became a ‘forgotten conflict’

China undermines its interests by boosting support for Myanmar’s faltering junta

Caveat creditor: China offers a financial lifeline to Myanmar’s junta

In early November, the Burma People’s Liberation Army (BPLA) and Karen National Liberation Army captured 17 soldiers and killed 14 more in skirmishes near Hpapun township in Karen state, after taking a military base on the Thai border the previous week.

Over-reliance on airpower

The brunt of the military’s operations has been in the ethnic majority Bamar heartland. With the BLPA expanding their footprint in the region, the military has acted with utmost barbarity, massacring civilians, arsoning homes, and leaving heads on stakes in Budalin village in Sagaing.

With improvements in their own drone technology, the junta’s forces are starting to grind back lost territory. Drones are now used in almost all operations, with improved effectiveness.

Despite the augmentation by conscripts, they are facing defections, surrenders with a growing number of people evading conscription altogether.

The regime’s number three, who is in charge of the conscription program, has publicly threatened punishments for those who evade mandatory service.

The military is increasingly reliant on air power, which has led to the death of over 540 civilians and 200 schools in the first 10 months of 2024, alone. The most recent strike targeted the ruby-mining town of Mogoke, which the TNLA seized in July.

But opposition gains have put those airbases in range. On November 5, a drone dropped a bomb at the airport in Naypyidaw soon after Min Aung Hlaing and his delegation departed for Kunming. On November 11, opposition forces fired rockets into the Shan Te airbase in Meiktila township.

Meiktila is a major military hub with several bases and defense industries, and the airbase is the hub of Air Force operations in northern Shan, Kachin, Sagaing and Sagaing regions.

There is now satellite evidence that the military is making improvements to a small airfield in Pakokku, just across the Irrawaddy River to the southwest of Myingyan, a major logistic and energy transit hub in Mandalay province where opposition forces have stepped up attacks.

The regime appears to be moving to smaller airfields in strongholds, which would allow it to save fuel in operations. It also suggests that they are increasingly reliant on riverine transportation to get jet fuel safely delivered.

Now in the dry season, the military sees a window of opportunity to regain territory lost since Operation 1027 began a year ago. Min Aung Hlaing has secured additional Chinese assistance, despite Beijing’s misgiving about his competence.

But that support may be insufficient across so many distinct battlefields, against an opposition that has demonstrated their refusal to kowtow to Beijing.

Zachary Abuza is a professor at the National War College in Washington and an adjunct at Georgetown University. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of the U.S. Department of Defense, the National War College, Georgetown University or Radio Free Asia.