Quite soon, possibly to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the Khmer Rouge takeover in April, Cambodia will pass a new law making it a jailable offense of up to five years to “deny, trivialize, reject or dispute the authenticity of crimes” committed during that regime’s 1975-79 rule.

The bill, requested – and presumably drafted – by Hun Sen, the former prime minister who handed power to his son in 2023, will replace a 2013 law that narrowly focused on denial.

The bill’s seven articles haven’t been publicly released, so it remains unclear how some of the terms are to be defined. “Trivialize” and “dispute” are broad, and there are works by academics that might be seen as “disputing” standard accounts of the Khmer Rouge era.

Is the “authentic history” of the bill’s title going to be based on the judgments of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia? If so, there will be major gaps in the narrative.

Cambodia’s courts are now so supine that one presumes the “authentic history” will be whatever the state prosecutor says it is, should a case come to trial.

There are two concerns about this.

First, the Cambodian government is not being honest about why it’s pushing through this law.

There is some scholarly debate about the total number of deaths that occurred between 1975 and 1979, and estimates range from one to three million.

There also remain discussions about how much intention there was behind the barbarism or how much the deaths were unintended consequences of economic policy and mismanagement.

No nostalgia

Yet, in Cambodian society, it’s nearly impossible to find a person these days who is worse off than they were in 1979, so there’s almost no nostalgia for the Khmer Rouge days, and the crude propaganda inflicted on people some fifty years ago has faded.

There are no neo-Khmer Rouge parties. “Socialism”, let alone “communism,” is no longer in the political vocabulary. Even though China is now Phnom Penh’s closest friend, there is no affection for Maoism and Mao among Cambodians.

Moreover, as far as I can tell, the 2013 law that covers denialism specifically hasn’t needed to be used too often.

Instead, the incoming law is quite obviously “political”, not least because since 1979, Cambodia’s politics has essentially been split into two over the meaning of events that year.

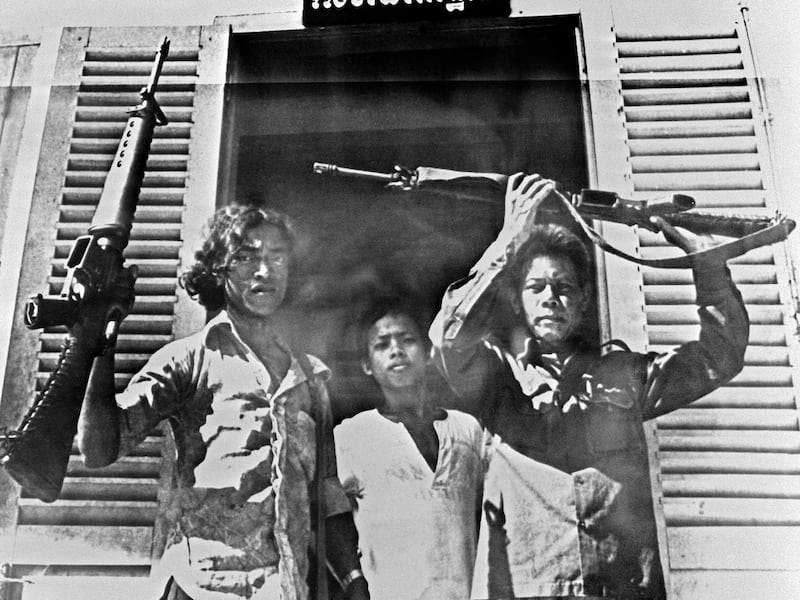

For the ruling party – whose old guard, including Hun Sen, were once mid-ranking Khmer Rouge cadre but defected and joined the Vietnam-led “liberation” – 1979 was Cambodia’s moment of salvation.

For today’s beleaguered and exiled political opposition in Cambodia, the invasion by Hanoi was yet another curse, meaning the country is still waiting for true liberation, by which most people mean the downfall of the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) of Hun Sen and his family.

The CPP is quite explicit: any opposition equates to supporting the Khmer Rouge. “You hate Pol Pot but you oppose the ones who toppled him. What does this mean? It means you are an ally of the Pol Pot regime,” Hun Sen said a few years ago, with a logic that will inform the incoming law.

Crackdown era

The ruling CPP has finished its destructive march through the institutions that began in 2017 and is now marching through the people’s minds.

A decade ago, Cambodia was a different sort of place. There was one-party rule, repression, and assassinations, yet the regime didn’t really care what most people thought as long as their outward actions were correct.

Today, it’s possible to imagine the Hun family lying awake at night, quivering with rage that someone might be thinking about deviations from the party line.

Now, the CPP really does care about banishing skepticism and enforcing obedience. What one thinks of the past is naturally an important part of this.

Another troublesome factor is that, with Jan. 27 having been the 80th anniversary of Holocaust Remembrance Day, there is a flurry of interest globally in trying to comprehend how ordinary people could commit such horrors as the Holocaust or the Khmer Rouge’s genocide.

The publication of Laurence Rees’ excellent new book, The Nazi Mind: Twelve Warnings from History, this month reminds us that if “never again” means anything, it means understanding the mentality of those who supported or joined in mass executions.

Yet we don’t learn this from the victims or ordinary people unassociated with the regime, even though these more accessible voices occupy the bulk of the literature.

RELATED STORIES

Home of notorious Khmer Rouge commander attracts few tourists

Final Khmer Rouge Tribunal session rejects appeal of former leader Khieu Samphan

Nuon Chea Dies at 93, Ending Hopes of Closure For Cambodia’s Victims of Khmer Rouge

Listen only to the outsider, and one comes away with the impression that almost everyone living under a despotic regime is either a passive resister or an outright rebel. There are a few devotees who find redemption after realizing their own sins – as in the main character in Schindler’s List.

Yet no dictatorship can possibly survive without some input from a majority of the population. Thus, it’s more important to learn not “why they killed,” but “why we killed” – or “why we didn’t do anything.”

Remembrance is vital

The world could do with hearing much more about other atrocities, like Cambodia’s.

For many in the West, there is a tendency to think of the Holocaust as a singular evil, which can lead one down the path of culture, not human nature, as an explanation.

One lesson of the 1930s was that the people most able to stop the spread of Fascism were the same people least capable of understanding its impulses.

The left-wing intelligentsia was content to keep to the position until quite late that Fascism was just a more reactionary form of capitalist exploitation, while conservative elites had a self-interest in thinking it was a tamable version of Marxism.

Their materialism, their belief that life could be reduced to the money in your pocket and what you can buy with it, didn’t allow them to see the emotional draw of Fascism.

These intense feelings brought the torch parade, the speeches, the marching paramilitaries, the uniforms and symbols, the book burnings, and the transgressiveness of petty revenge and bullying.

Perhaps the best definition of Fascism came from Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky, who said: “there lives alongside the twentieth century the tenth or the thirteenth. A hundred million people use electricity and still believe in the magic power of signs and exorcisms.”

Likewise, the same people now who were supposed to stop the rise of new despotisms have been as equally ignorant about the power of signs and exorcisms.

Europe kidded itself that Russian strongman Vladimir Putin was as much a rationalist as Germany’s Angela Merkel.

The notion that all the Chinese Communist Party cared about was economic growth blinded world leaders to its changing aspirations: Han supremacy, jingoism, revenging past humiliations, national rebirth and territorial conquests.

In Cambodia, it is possible to find books by or about Khmer Rouge perpetrators, yet the curious reader must exert a good deal of effort.

Those who do that find that a temperament for the transgressive and the cynical motivated the Khmer Rouge’s cadres.

It won’t be long before the world marks a Holocaust Memorial Day without any survivors present at the commemorations.

Cambodia’s horror is more recent history, yet anyone who was a teenager at the time is now in their sixties. We haven’t too long left with that generation.

Even aside from the clear political reasons for introducing the new law, it might give historians pause before writing about the more gray aspects of the Khmer Rouge era – or exploring the motives of the perpetrators.

Once it becomes illegal to “condone” the Khmer Rouge’s crimes, whatever that means, revealing what one did as a cadre could skirt the border of criminality.

My fear is that the law will confine history to the study of what the Khmer Rouge did, not why it did it. This would be much to the detriment of future generations worldwide.

David Hutt is a research fellow at the Central European Institute of Asian Studies (CEIAS) and the Southeast Asia Columnist at the Diplomat. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of RFA.