Norbu was only 17 the first time he helped smuggle Tibetans out of Tibet. One cog in a well-oiled machine, Norbu — who is being referred to as a pseudonym for security reasons — played the role of a guide. His job was to meet small groups of escapees at the Dram border (Zhangmu) in southwest Tibet and lead them along remote pathways into the safety of Nepal. All were fleeing Chinese repression back home.

To avoid patrols on both sides of the border, their only option was to take strenuous mountain routes during the middle of the night. After three or four hours of trekking, they’d reach a village safe house. There, the group would await cars to take them the rest of the way to Kathmandu, where they could be registered and processed by the Tibetan government-in-exile’s reception center.

“There was one Tibetan who was so frightened that even when we reached the house in the village he was still trembling,” Norbu recalled in a recent interview, raising his voice as he mirrored the mournful cry the man made.

A member of Nepal’s Sherpa ethnicity, Norbu, now 33, grew up in the Himalayas — which has long served as a natural border between Tibet and Nepal. His shared background and his Nepalese-accented Tibetan made him a good fit for the shadowy job of a smuggler.

The term “smuggler,” however, is rarely used by Tibetans, who call men like Norbu lamtikpa (ལམ་འཁྲིད་པ།), which means guide in Tibetan.

That word hints at how these individuals have been a lifeline for refugees over the past 65 years. Since 1959, when the Dalai Lama and around 8,000 Tibetans were forced to escape to India after Communist China’s takeover of Tibet, tens of thousands of Tibetans have been smuggled out of the country.

For Tibetans, this journey to Nepal and then India represents a crucial path to freedom, a chance for a better life, and an opportunity to see their living god, the Dalai Lama. But for most it is also a deeply painful journey, as more often than not leaving means never returning home again.

“They look exhausted and they often pray to God for freedom. I feel sad seeing their suffering, but there’s nothing I can do to ease their pain,” Norbu said. “All I can offer is reassurance, saying, ‘Don’t worry, you’re in Nepal now, and it’s a safe place,’ hoping to calm them. That’s all I can do.”

RELATED STORIES

China’s controversial boarding school policy for Tibetans explained

China bans monks, aid workers from visiting quake-hit areas of Tibet

China blocks use of Tibetan language on learning apps, streaming services

A shrinking stream of Tibetan refugees

Norbu worked as a smuggler from 2009 to 2015 – years that traced the start of a precipitous decline in crossings as a result of tightening border restrictions and increased surveillance within Tibet. He stopped when those restrictions grew even tighter in the wake of the April 2015 earthquake in Nepal.

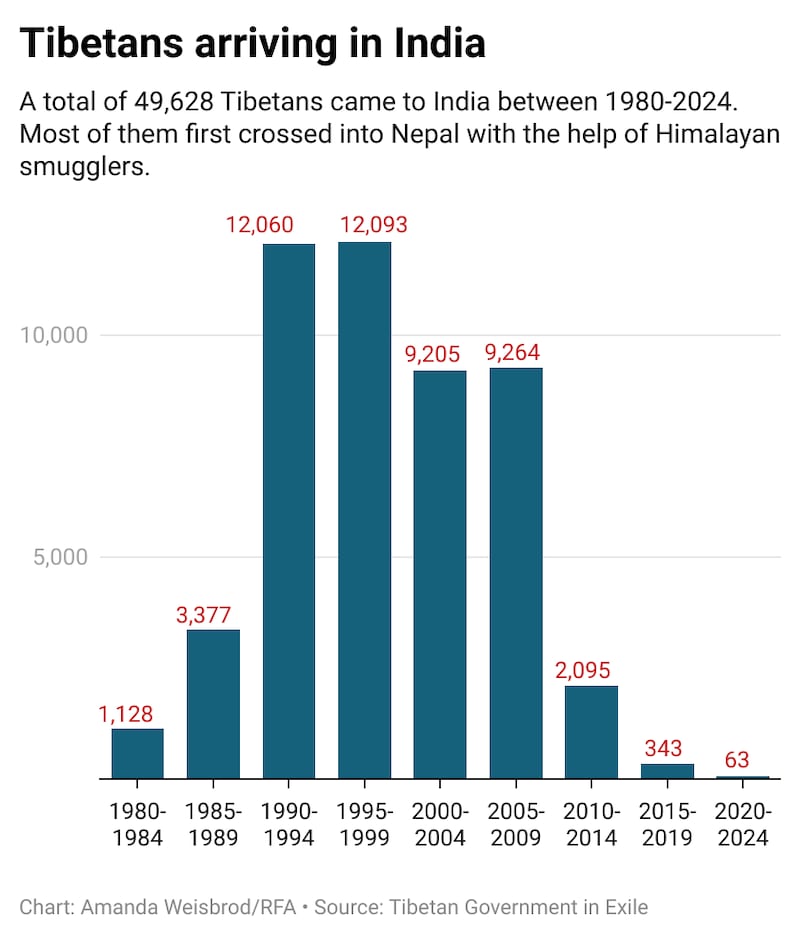

Data from the Tibetan government-in-exile shows that about 1,000 Tibetan refugees crossed each year in the first decade of the century. From 2010 to 2014, that number dipped to about 400 a year, and 70 in the following half-decade. Only 55 Tibetans in total have crossed since 2020, including just 8 who crossed last year.

In the mid-1990s, when he was 7, Rinchen Dorjee was smuggled to India along with 28 other Tibetans. They took the famous Nangpa la pass, a crossing less than 20 miles from Mt. Everest, to reach Nepal — a journey that lasted over a month, including a week of walking through the snow.

“As we neared the Nepal border, we had no food left, and survived on just drinking tea leaves for two days,” recounted Dorjee, who is now 36, living and working in Dharmasala, India.

Eventually, they found a village and their guide bought a sheep and slaughtered it. But someone had alerted the authorities, Dorjee learned, and the group was forced to flee before they even had a bite of meat.

“When a flashlight from the Chinese border tower swept our way, we had to lie still in the grass, moving only when it passed,” he recalled.

Dorjee’s experience of transiting in a large group reflects how Tibetans fled throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Until the early 2000s, individual smugglers would move 20 to 30 Tibetan refugees at a time. Unlike the network system Norbu was part of years later, these individuals took full responsibility for completing the journey from start to finish, according to people familiar with the journey who spoke to RFA.

In 2008, rare public protests against Beijing’s rule in Lhasa and elsewhere culminated in mass arrests and as many as 140 killed by security forces, according to figures from rights groups. As a result of the uprising, China tightened border restrictions; implemented strict surveillance systems along the Tibet-Nepal border; and exerted pressure on the Nepalese government to prevent Tibetans from crossing. Crossing the border became more dangerous, particularly in large groups.

After that, smugglers like Norbu began operating within larger networks that had leaders and agents spread across Tibet, Nepal and even China. These agents would collect Tibetans fleeing from places like Lhasa and Shigatse and pass them along to other smugglers.

“We divided ourselves into two groups,” said Norbu. “One group would move ahead to scout the path and signal the way forward. They used the small flashlight from a Chinese lighter, which served as a beacon to guide us in the dark. The narrow beam of light would send a signal, and we would carefully follow its direction.”

Norbu’s unit consisted of three Sherpas whose role was to transport escapees from hiding spots during the night, often in remote rocky mountain caves, and guide them safely to Nepalese villages. He was only paid 3,000 Nepalese rupees per day (about $30 in 2014) from their network agent group, but even that meager sum was better than what he earned in his previous job as a porter, where he made only a sixth as much.

Certainly, the risks were much higher. “Whenever the mission started, there was a sense of fear,” he said.

“Sometimes, when we went to get the Tibetans, they were suspicious, unsure if we were police. They would stay hidden in the forest and not come out easily. We had to reassure them that we were there to help and on their side. The Tibetans rarely spoke or asked questions,” Norbu said. The youngest person he smuggled was just 13, the oldest nearing middle age.

Separation, longing and exiled life

Around 7,000 Tibetan refugees now live in Dharamshala, the northern Indian hill town that since 1959 has served as the spiritual, cultural and political center of the Tibetan diaspora.

Most of those living here carry a story of emotional separation.

Tsering, 30, an office assistant for the Tibetan government-in-exile, was raised by his father who arranged to have the boy smuggled to India at the age of 11 by paying 7,000 Chinese yuan ($850) in 2005.

While Tsering assumed he would one day reunite with his family, his father’s recent death from a car accident has left him unmoored. He learned of it from his aunt in Dharamshala, who was able to remain in touch with some family back home.

“I have always yearned to return to Tibet and to be with my father but the tragic news turns everything’s empty, I feel there are many words left unspoken, which makes me feel lonely,” he said.

Since 1980, nearly 50,000 Tibetans have arrived in India and Tibet as refugees. Globally, there are about 150,000 Tibetans in the diaspora, with the majority born in exile.

Family separation is the norm for nearly all who left the country through smuggling routes. Those who leave as children may have relatives on the other side of the border, but many arrive alone. The school system in Dharmasala is run with that in mind, with most students housed in dormitories run by foster parents who focus on caring for the emotional needs of new arrivals and integrating them among the community.

But in spite of those efforts, some Tibetan refugees struggle with trauma and depression as a result of family separation — even decades after leaving their homeland.

Not far from the offices of the exile government, a narrow road leads to the Kunphen Recovery Center, a drug rehab center set in a northern Indian-style hostel adorned with Tibetan prayer flags and surrounded by a gated compound with barbed wire.

Unlike some drug rehab centers, there are no guards here and patients are free to roam inside the compound. Treatment involves lectures from Buddhist monks, yoga, meditation and traditional Tibetan arts.

Today, Dorjee has a good job as a night guard for the residence of the Sikyong, or president, of the exile government. But not too long ago he was a patient at Kunphen. After he was smuggled to India at 7, he spent his childhood haunted by homesickness. As he got older, the stress of separation pushed him to pills and marijuana.

“If I had stayed in Tibet, I think I wouldn’t have been involved in drug addiction because my parents and all the relatives are there … they would definitely stop me from doing wrong things,” said Dorjee, recalling that he was sent to India only after his aunt convinced his parents it would afford him better opportunities.

Changes in China’s Tibet policy that began in 2008, have accelerated since Chinese president Xi Jinping took office in 2013. Beijing has drastically increased the deployment of soldiers and continued to build infrastructure along Tibet’s border, building new border villages which are filled with both Tibetans and relocated Han Chinese. High-tech surveillance systems have made free movement more difficult than ever.

With fewer Tibetans able to cross, the diaspora in India and Nepal has drastically declined, hollowing out both monasteries and schools.

“Increasing Chinese restrictions have strained family relationships and has had a negative impact on exiled schools and monasteries,” Sikyong Penpa Tsering said in November 2024 at a public gathering.

“Last year we received only four students from Tibet, but this year not a single student from Tibet has been enrolled, ” Tsultrim Dorjee, the general secretary of Tibetan Children’s Village, or TCV, told RFA in late 2024.

For those who have made it to India relatively recently, many cited education as a driver of their move. One key aspect of China’s Tibetan policy has been replacing Tibetan education with Mandarin-only schooling, as part of a forced assimilation program that has seen monasteries shuttered and children pressed into abusive boarding schools.

Sonam Dharkyi, an 11th grader at TCV, left Tibet in 2014.

“We didn’t have a proper school in my village, but I dreamed of going to school. Now, I’m getting a modern education and [studying] Tibetan as well, which I never would’ve known if I stayed back home in Tibet,” she told RFA.

To make it to India, Sonam and five others walked for more than 20 days to reach the Nepal border, crossing slippery patches of ice, treacherous rivers and rickety bridges in the Himalayan mountains. Along the way, they slept in mountain caves.

“I remember feeling hungry and freezing through the night,” she recounted. “With no choice, we had to cross the steep slopes and rugged valleys, and I feared slipping to my death, unsure if I could complete the journey.”

A decade after her arrival, Sonam dreams of being a doctor. Today, she can look forward to a future that would have been unimaginable under Chinese rule.

For Norbu, the former smuggler, helping Tibetans access hope for the first was a rich reward.

“I must say that this is the best job I did in my life so far as well as on a humanitarian level,” Norbu told RFA. “I cannot express that joy over here how I felt when I was able to help them make their journey to Nepal.”

Additional reporting by Abby Seiff. Edited by Abby Seiff and Boer Deng.