Read about this topic in Vietnamese.

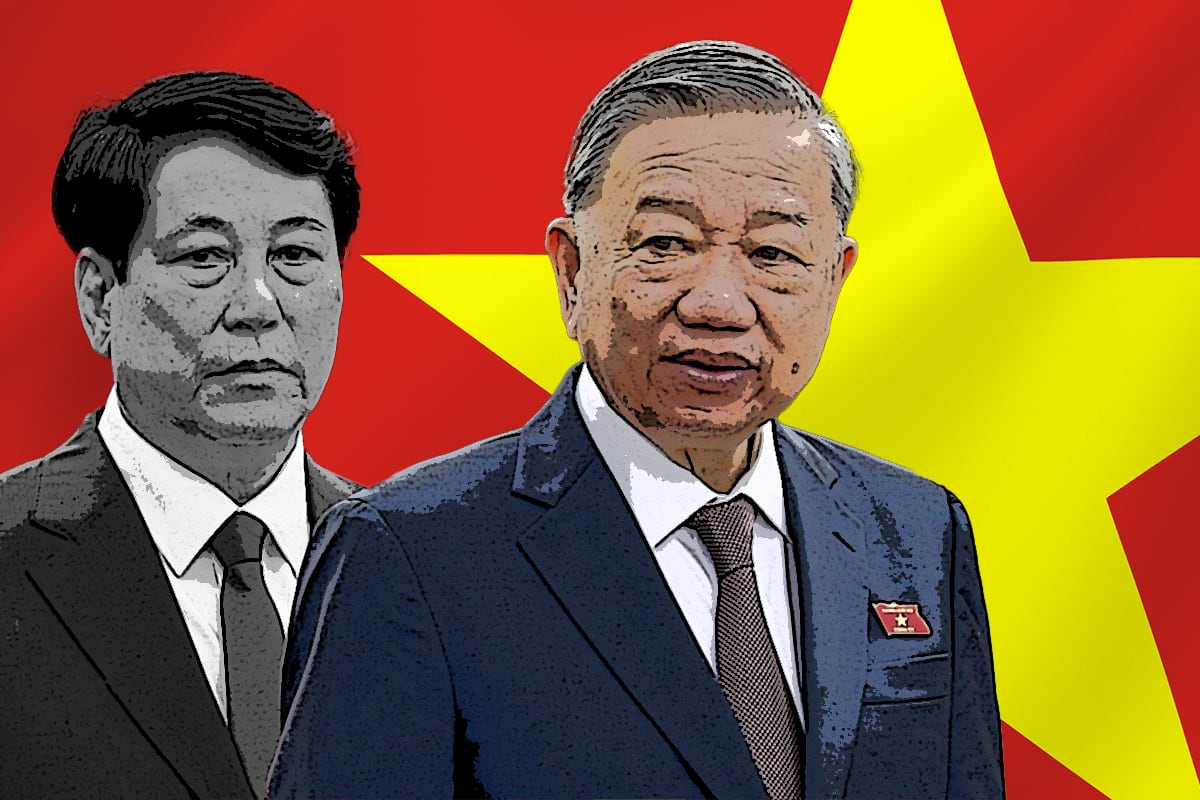

Since becoming general secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam, To Lam has drawn international attention with his aggressive plans for cost-cutting within the government but he’s been quiet about another drain on the state budget – the ruling party itself.

After taking office last August, he has moved this year to eliminate and merge ministries and central government agencies, reduce the number of provinces and cities by half, and dismantle district-level administrative units. Tens of thousands of civil servants have already lost their jobs. The Ministry of Interior has estimated that in five years, this will have saved 130 trillion dong (US$5.2 billion at today’s exchange rate) in the state budget.

To Lam’s campaign has been likened to the drastic cuts that U.S. President Donald Trump and tech billionaire Elon Musk have made to U.S. federal agencies through the Department of Government Efficiency.

But when it comes to making savings in Vietnam’s state apparatus, To Lam appears to have hedged his bets.

Vietnam operates under two intertwined systems: the party and the government. Although each has a separate budget, both draw from the same source — taxpayer money. The party, in power since the end of the Vietnam War and the reunification of the country in 1975, exists as a parallel structure to the government and plays the leading role in policymaking and governance.

While the government’s budget is occasionally made public, the party’s finances remain classified under Vietnamese law.

This policy predates To Lam’s leadership. However, given his sweeping efforts to streamline the state apparatus and reduce spending, his silence on the party’s own budget raises questions about how far he’s willing to go on fiscal reform.

Vu Tuong, a professor and expert on Vietnamese politics from the University of Oregon, said data shows that from 2008 to 2015, the Central Party Office’s budget increased steadily.

“Although actual spending figures are not disclosed, the Central Party Office alone saw its planned budget quadruple in seven years — from nearly US$27 million (622 billion dong) in 2008 to about US$105 million (more than 2,400 billion dong) in 2015,” he said.

The office functions as the party’s command center, where the general secretary oversees both party and government operations. From 2011 to 2015, its budget rose by 180 percent — three times higher than the increase in the government office’s budget, according to Vu Tuong. The publication of data on its spending stopped in 2015.

Budget is a secret

Zachary Abuza, an expert on Southeast Asia at the National War College in Washington, noted the lack of transparency.

“The party’s budget is a secret, so researchers must work with imperfect data,” he told Radio Free Asia. He said To Lam is mindful of ballooning recurrent expenditures and has made some attempts to rein them in. For example, the party’s foreign affairs committee has been merged into other entities. However, despite these changes, the party’s overall budget continues to grow.

“While the budgets of government agencies have shrunk or stagnated, the budget for the CPV’s bureaucracy has steadily increased over the past few years, if we count the Fatherland Front, the organization that supports the party’s activities,” Abuza said. CPV stands for the Communist Party of Vietnam.

He said more transparency could help improve the party’s legitimacy, but given its obsession with maintaining supreme power, “it’s hard to see them cutting the party’s budget,” he said.

In 2016, the Vietnam Institute for Economic and Policy Research estimated that the economic cost of maintaining public mass organizations — directly controlled by the Communist Party — ranged from 45,600 to 68,100 billion dong annually (about US$2 billion to US$3 billion at the time). These organizations are intended to fulfill roles that, in democratic countries, would be played by independent civil society groups. To Lam has not indicated whether he intends to cut their funding.

According to Abuza, To Lam’s ongoing radical restructuring of the national government, including the consolidation of five ministries and several government agencies, and the reduction of nearly 50% of the number of provinces, created a rare opportunity to further cut both state and party organizations.

However, the budgets for the party and its supporting organizations are difficult to cut because they are tied to the inherent interests of the bureaucracy, he said.

There may be a political reason behind To Lam’s reluctance to target the party’s spending.

The next National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam is approaching in early 2026, when a new generation of leaders will be elected. To Lam, 67, is believed to be seeking another term as general secretary.

“There’s only half-a-year left until the Party Congress,” said Abuza. “So there won’t be any major changes. Normally, spending and policy implementation would be completely locked down by this stage.”

Edited by Mat Pennington.