Luck got him through the Pol Pot years – and across the border to safety

For Poly Sam, surviving the Khmer Rouge was just the first challenge. Four years in a refugee camp came next.

March 20, 2025

Poly Sam was 11-years-old when the Khmer Rouge marched into Phnom Penh on the same day as the traditional Khmer New Year holiday.

“It was meant to be a day of celebration, but it turned out to be a very, very bad day, and the beginning of a very bad time for many Cambodians,” he recalled recently.

April 17 marks the 50th anniversary of the Khmer Rouge’s victorious arrival in Cambodia’s capital. For Cambodians, it’s a day remembered for its horrific beginnings.

Within a handful of years, as many as 2 million people would be dead at the hands of the Pol Pot-led regime.

“You know, for me, there’s a lot of negative memories,” Poly said. “But it’s a memory that I can share with people because we don’t want anyone to go through this again.”

From Khmer Rouge survivor to a Thai refugee camp, and later as a teenage migrant to the United States, Poly encountered more than most people over five decades.

He witnessed unspeakable acts and extreme deprivation. And he survived when so many others did not.

“I’m lucky,” he said. “A lucky son of bitch.”

Before the Khmer Rouge, Poly’s brother, Sien Sam, was a school teacher who later became a soldier for Cambodia’s short-lived Lon Nol regime – the military dictatorship that was ousted in 1975.

Sien was one of the first to die as the Khmer Rouge forced everyone to walk out of Phnom Penh and into the countryside, Poly said.

Outside of the city, Khmer Rouge soldiers marched Sien away to be “re-educated.” Only later as the “disappeared” grew in number, never to return, did people begin to understand what was happening, according to Poly.

“He was probably killed in the first or second week. But we don’t know; nothing could be verified,” he said. “Until this day, we still don’t know where he died.”

Tricks for survival

Today, Poly lists why he is lucky: Lucky to have only lost four or five members of his family. Lucky to have never been tortured. And lucky to have endured.

“It’s very fortunate for a kid. You are in the field all the time, so you are able to scavenge a lot of things,” he said.

“You learn a lot of tricks on how to survive. For example, you catch the fish, you wrap the leaf around the fish, and you put it under the ground and you burn a fire on top. When nobody is around you pull it out and eat it.”

Surviving the Khmer Rouge was one thing, but escaping from Cambodia to Thailand was another.

He begged his mother to allow him to try to flee his country. She had lost her oldest son to the Khmer Rouge. Her two other sons were already living in the United States, and now she feared she was about to lose her last born.

Poly risked his life to flee the country, carefully making his way across Cambodia from one internally displaced person’s camp to another.

The last hurdle was the greatest: sneaking into a refugee camp on the Thai border that was tightly controlled by Thai soldiers authorized to shoot anyone on site.

The only way in was under the cover of darkness. Poly described his most dangerous moment and the lengths and depths of what it took to survive as a teenager.

The first hurdle was slipping under the barbed wire fences without being noticed by the Thai soldiers. Once inside the camp, the next challenge was to hide out of sight until United Nations workers took over control of the camp during daylight hours.

Poly hid in the one spot that no one would look: the communal pit latrine. He threw himself into it and waited for hours until it was safe to emerge.

‘Nobody can undo it’

After four years in the camp. Poly was brought to the United States in 1983. More than 100,000 Cambodians settled in the United States between 1979 and 1990. A total of more than 1 million fled Cambodia during the years of civil war and turmoil.

An American family informally adopted Poly, sent him to high school, and later helped him obtain a social worker degree at college.

He worked at that for seven years before joining Radio Free Asia’s Khmer service in 1997. He now leads the Khmer service as its director.

Can he forgive?

“Whatever happened in the past, nobody can undo it. We have to look to the future, so I will forgive,” he said.

“I have forgiven the Khmer Rouge. Some of them were victims themselves. So there’s no need to hold grudges against them.”

But he says it is a different story for former Khmer Rouge cadres who continue to hold and abuse power in Cambodia today: “It is very difficult to forgive them.”

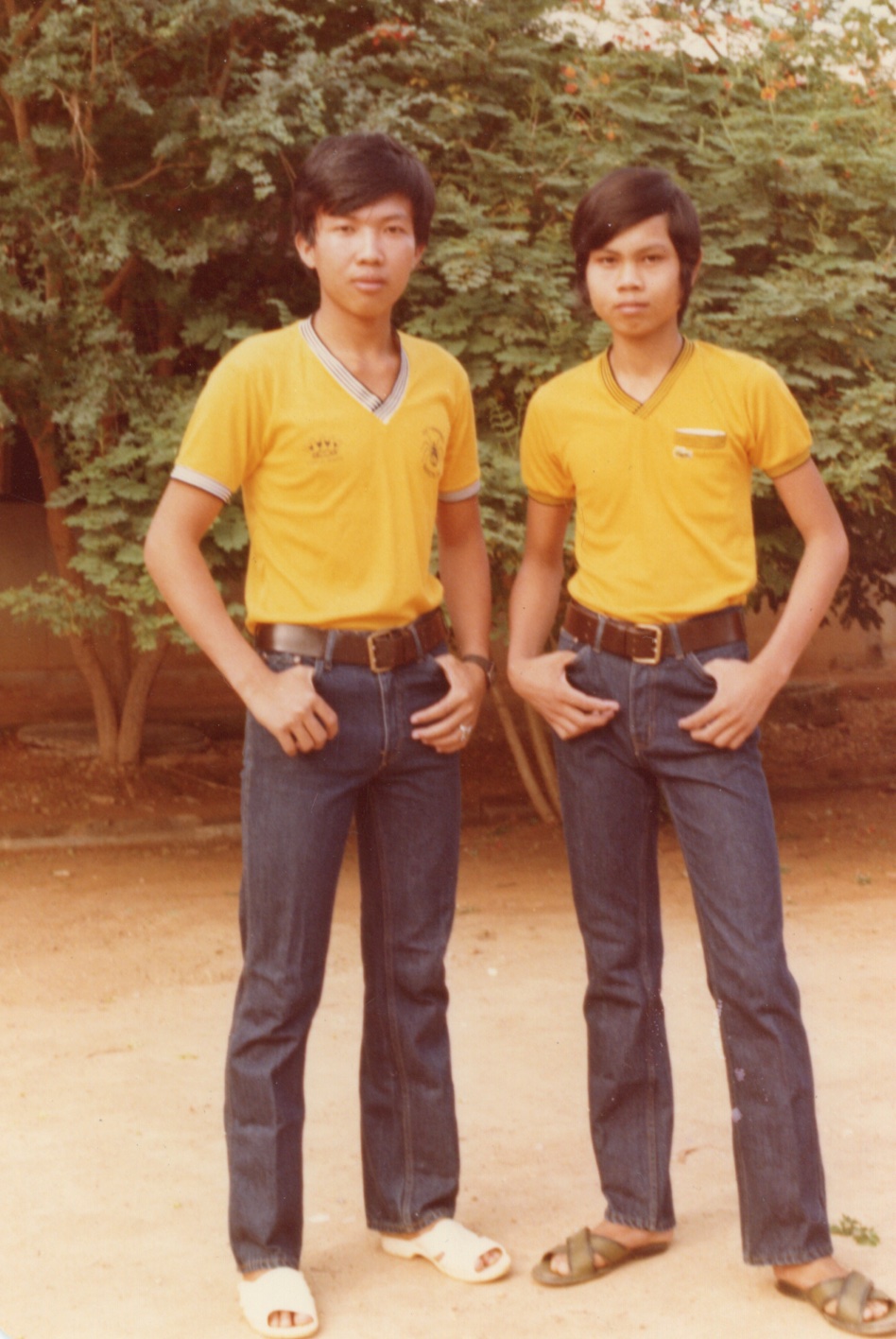

Family tribute

Sam Sien, brother, died 1975

Yu Yon, brother-in-law, died 1975

Pich Bo, brother-in-law, died 1975

Pich Koy, nephew, died 1975