A family separation and countless encounters with death

Vuthy Huot remembers listening to what he thought was his last breath. Now, he credits his survival to holding onto hope.

March 20, 2025

The parents waved goodbye to their tearful 13-year-old son. The father patted the boy on the shoulder, reassuring him that he would return soon.

There was no hiding that the parents of Vuthy Huot were overjoyed to be returning to Phnom Penh. It had been six weeks since the family was forced out of their home and marched out of the city.

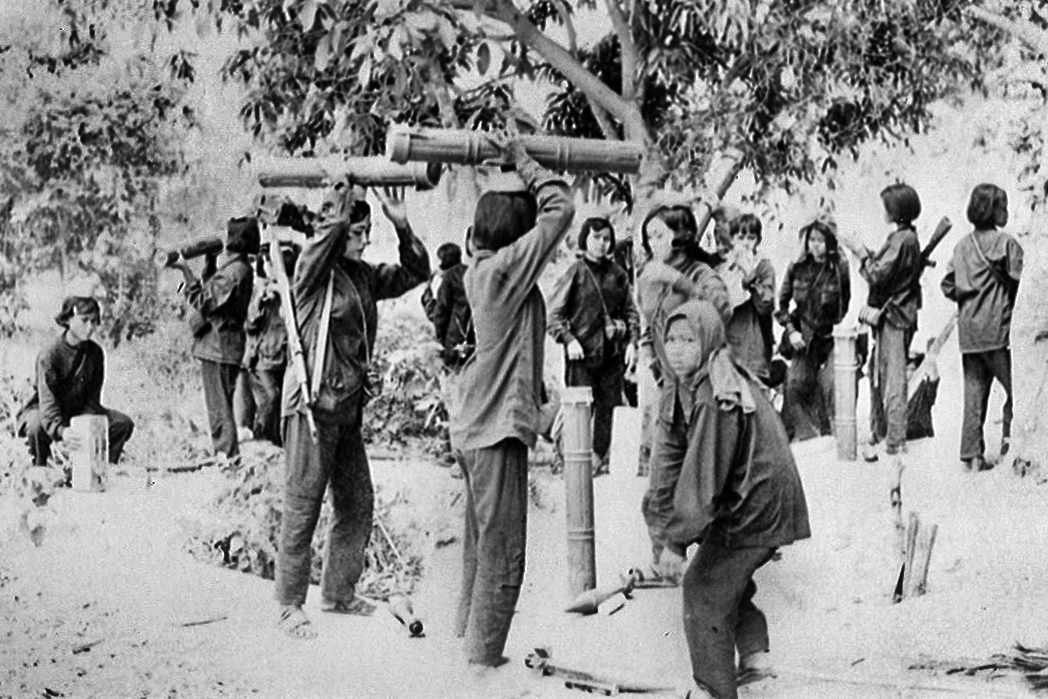

A mass trauma event. Two million inhabitants evacuated overnight, creating a ghost city in their wake.

Now, the son was being asked to stay behind in a rural village, and for the first time in his life, Vuthy was being separated from his parents. He was told he was the only one his father could trust to care for his elderly grandmother.

“I was very upset. That was the first time I was separated from the family,” Vuthy said recently from his office at Radio Free Asia’s Washington headquarters. “But my father tapped me on my shoulder and said, ‘Stay strong, we will come back and get you as soon as we settle down in Phnom Penh.’”

The 'new people'

The past weeks had first offered excitement for a young city boy who thought he was about to have the chance to go to the countryside with his family.

“I was very happy that I would spend time with my family and would see the countryside. But soon all the happiness and joy disappeared,” he said.

During the walk out of Phnom Penh, Vuthy watched helplessly as both his father and brother-in-law were separated from their family group. Khmer Rouge cadre, who had first been friendly, then angry, took the two men aside, tied their hands with rope, then strung them together and marched them away from the family.

“They walked at almost the same time along the road with us, so I could see them probably for the first few days,” he said.

Vuthy believes adult men were separated from their families to facilitate the evacuation.

Vuthy and his other family members made it to the village in Prey Kabas commune, Takeo province – about 90 km (56 miles) from the capital. His father and brother-in-law would arrive in the village shortly afterward.

In the days to come, Khmer Rouge cadre began vetting the “new people,” the disparaging name given to evacuees from the city.

Vuthy said his father told the truth: He was a skilled cartographer. Surprisingly, his reply was welcomed.

“The Khmer Rouge people stood up and said ‘We need your skill. We want you to come back and work for Angka.’”

They considered us traitors

As quickly as they had arrived in the village, his father, mother and three of his brothers were turned around to return to Phnom Penh.

Days later, his sister was also taken away. Both she and her husband were sent to work in the fields.

Still in the village, Vuthy’s immediate mission was to learn how to keep himself and his grandmother alive.

“I didn’t know how to catch a fish, frog, crab or snake,” he said. “And as a newcomer, nobody wanted to talk to us, because they considered us traitors.”

He also didn’t know how to cook, and his grandmother, a staunch Buddhist, refused to kill anything that was alive. When he did manage to catch fish and crabs and brought them to the kitchen, she wouldn’t touch them.

It was only a matter of weeks after his parents left that his grandmother died of starvation. He was now alone. He vowed he would live to be reunited with his parents.

The first year under the Khmer Rouge was the most difficult. Vuthy was sent to work in the rice fields. There was a massive flood in the first wet season, and food was scarce.

He was settled alongside a river in northwestern Cambodia where he lived on an elevated bamboo platform. Scores of other platforms were nearby, divided into family groups. As the rain fell, the river rose until the platforms were surrounded by water.

He remembers the leeches and the kindness of a woman he called Aunty Poh, who slept on the platform next to him with her three children. She cut up her skirt to make pants for him to protect him from the leeches.

“The Khmer Rouge people would come in the evening by boat and would distribute one bowl of rice per family,” he said. “If you had three people in a family, you would have three spoonfuls of rice. I was by myself, and I only had one spoon.”

Close to succumbing

That first wet season, the river remained high for two months. When he finally took off those pants to wash them, they were covered in the trails of hundreds of leeches. He had survived.

Aunty Poh, who made the pants for him, did not. Neither did her children. She kept the body of her last child next to her for days, to claim his meager rice allocation until she could no longer. Hunger killed both of them. Vuthy came close to succumbing.

“You know when people die of hunger, they usually die at around 3 or 4 in the morning,” he said.

That last rasping gasp is a sound he remembers himself making. It woke his neighbor, Aunty Poh. She opened his mouth with a spoon and fed him the rice porridge he had saved for the morning.

“When your body feels this porridge, you start to have feeling, you feel the food and you can move. I was still conscious, but I could not move.”

For Vuthy, many memories remain painful, but worse, there are others he can no longer summon.

“I don’t remember the faces of my parents or my brother or sister. I don’t have any photos left of any of them. The Khmer Rouge destroyed or burnt all photo albums.”

What made him survive when so many others did not, he attributes to one of the greatest human emotions – that of hope.

“If you have hope, you have the inspiration to stay alive, to fight and stay alive.”

‘At least I survived’

For four years, Vuthy held on, believing he would one day be reunited with his parents. When the Khmer Rouge were ousted from power in 1979, he walked back to the capital. Each day for more than three months, he would wait at the city gates, wanting them to walk into view.

Eyewitnesses who knew his parents told him what happened. They died not long after they left him behind in the village, and just before they reached Phnom Penh.

The boat transporting them by river to the capital had capsized in front of the Royal Palace. Overladen with people happy to be returning to the city, there had been a rush to one side of the boat. It lurched to one side and sank.

From that day to this, one thing has kept him going. A mantra that he tells himself often. It begins with “at least.”

“At least I survived. At least I survived and continued to represent my family. At least my family, my mother, my father, my sister and my brothers do not have to go through all the hardship that I did during the Khmer Rouge. At least, while they died horribly, by drowning, but at least they no longer suffered.”

In recent years, as an on-air host and deputy director of RFA’s Khmer service, Vuthy has watched as Cambodia has slid from a democracy to authoritarianism. That has been difficult to witness, he said.

“Go back to the history of Cambodia itself. It has gone through a lot,” he said.

”But if we don't keep fighting. We won't survive. We have only one life to live, and we all die sooner or later. Do something good. Do something for your country.”

Family tribute

Bun Huot, father, died August 1975

Khin Vanna, mother, died August 1975

Huot Lida, sister, died September 1978

Chhan Chhe, brother in-law, died August 1977

Huot Rithisak, brother, died August 1975

Huot Hun, sister, died August 1975

Huot Tin, brother, died August 1975

Huot Bunnarith, brother, died August 1975