Born in a darkened hospital as the Khmer Rouge took control

Sarann Nuon's earliest years were under the Pol Pot regime, and she only remembers fleeing to Thailand several years later.

March 20, 2025

In 1975, as the Khmer Rouge fanned out across the country, decimating their rivals and forcing people in their millions out of cities into the countryside, Sarann Nuon was busy being born.

The maternity ward at Battambang’s Friendship Hospital was suddenly plunged into darkness. The Khmer Rouge had entered the northwestern city, announcing their arrival by taking out the power. Sarann came into this world by torchlight.

“I was born the very day. April 17th, 1975, the day the Khmer Rouge invaded,” she said. “My family would say I’m a true Pol Pot baby.”

“Outside, the Khmer Rouge were shooting the lights out. Somehow, I was born as the electricity was going in and out and chaos was happening all around the country.”

Not long after they arrived in the city, the Khmer Rouge entered the hospital and ordered everyone out into the countryside “to be with Angkar,” as the nameless, faceless regime would quickly come to be known.

Overnight, loyalty to Angkar replaced all other forms – to parents, to family, to village or community, and even to religion.

People deemed disloyal to Angkar were to be “smashed,” a Khmer Rouge term for weeding out and murdering those deemed disloyal. Over the next four years, millions would die.

'Always hungry'

For Sarann, her mother and her family, the two days’ grace they had before being forced out of the hospital and into the countryside gave her mother a moment to recover and a fighting chance at survival for both of them.

“We were lucky, we had a family, who knew someone with a tractor, and they put me and my mother on that, and then all the other villagers just walked and walked,” Sarann said. “And being conceived before the war, I was born a very fat baby.”

Her nickname is “Map,” which translates to “fat.”

“My grandmother, aunts and uncles still call me ‘Map’ to this day,” she said. “My brother who was born at the end of the war wasn’t so fortunate. He was so malnourished, so skinny.”

Sarann has few memories of that time. The strongest memories are second-hand from what she gleaned from others.

“I just heard that I played in the dirt, and nobody was watching me, and I was just a dirty, fat baby. That’s my history. Always hungry,’ she said.

Her first real memory of Cambodia, which she claims as her own, is when her family decided to flee.

“My great-grandmother was dressing me, and I asked her where we were going. And the sarong she dressed me in had a gold necklace in the seam of the sarong. And I remember that so clearly,” she said.

“And I remember asking her if she was coming with us, and she said no.”

'If he was alive, we had no idea'

Sarann’s grandfather, who was heavily involved in local politics, had escaped Cambodia shortly after the Khmer Rouge seized power in 1975.

It took him two months to walk his way out of the country, staying out of sight and avoiding the Khmer Rouge, but he made it first to Thailand and then to the United States and avoided what was to come.

Hundreds of thousands of intellectuals, city residents, leaders of the old government and thousands of low-level soldiers, police officers and civil servants were murdered by the Khmer Rouge.

Bodies were dumped in mass graves in rural areas across the country, earning them the name of the “Killing Fields.”

Within days, the country became a closed-off nation for people inside and outside.

“If he was alive, we had no idea, and he had no idea whether we were alive. Not until the war ended when Vietnam invaded Cambodia and the refugee camps started to open,” Sarann said.

From America, where he had been granted asylum, Sarann’s grandfather never gave up hope through the dark years that his family would survive and be reunited.

After the regime was felled in 1979, her grandfather sent photos and a letter with a friend from Virginia who returned to Asia to work in one of the camps. Her grandfather hoped that his family would eventually get the message that he was still alive, and that he could sponsor them to join him in the United States.

Fled by bicycle and by foot

And so in 1980, 5-year-old Sarann, suddenly found herself being dressed in a sarong by her great-grandmother. A sarong in which a gold chain, the sum of the family’s wealth, was sewn into its hem.

“And then, just running, running, running and running. My uncle would carry me on his back, and my mother had my baby brother, who was a year and a half old,” she said.

They had travelled by bicycle and by foot from village to village until they got close to the border.

“With the gold, we exchanged it to hire a guide who knows how to get to the Thai border safely, to cross without the Khmer Rouge finding you and the Thai soldiers trying to shoot you, to kill you, and then the landmines.”

Their final push to freedom was made at night, a short journey that took more than five hours. She remembers being separated from her mother and brother at one point, as he started to cry and the group split up in case the noise of a baby crying gave them all away.

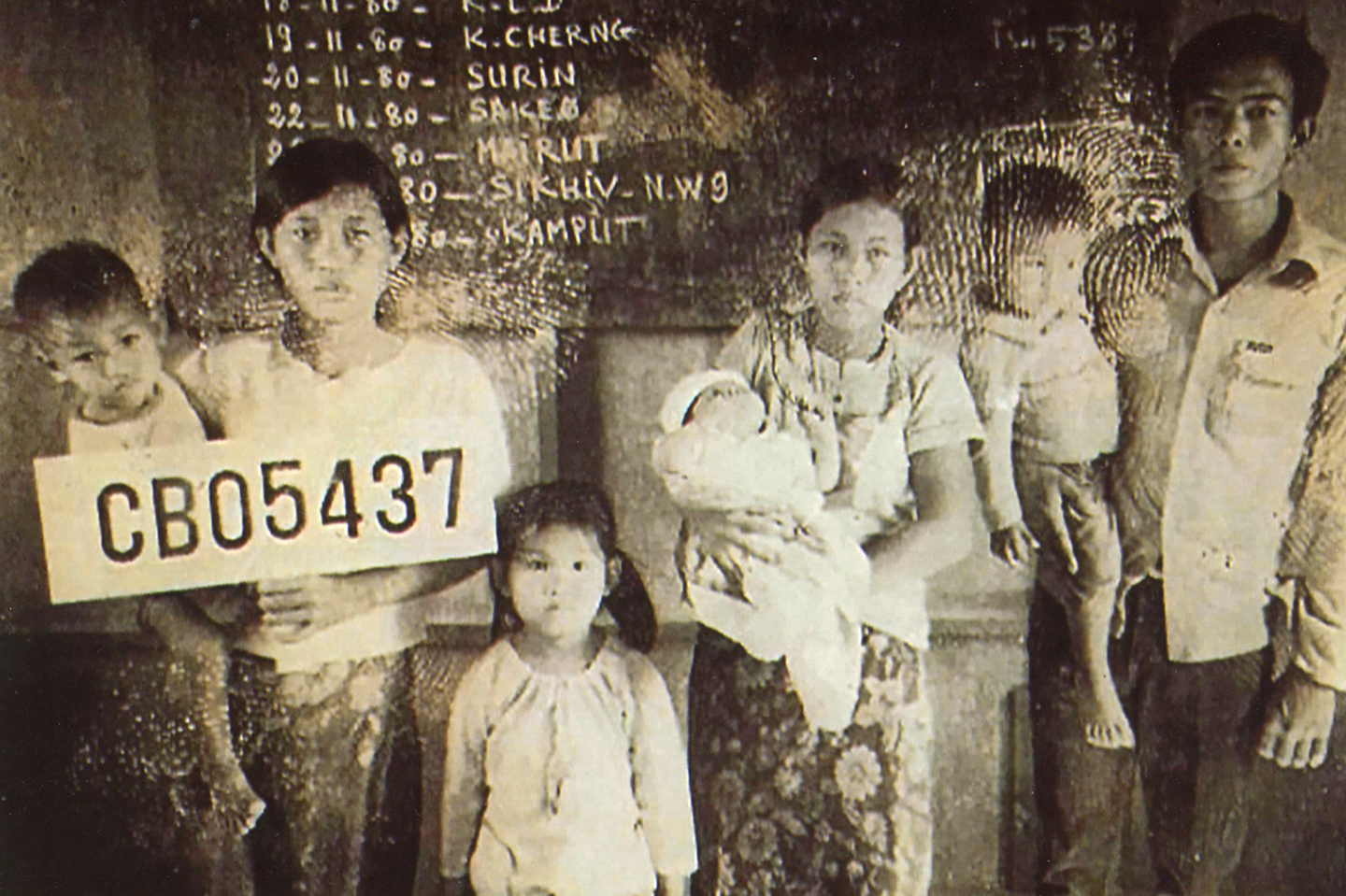

Together with her mother, brother, aunt, uncle and their two children, they eventually made it to safety inside the Khao-I-Dang border refugee camp. And from there, with her grandfather as a direct sponsor, they were among the first granted political asylum in the United States.

“We all know that our history kind of defines us,” Sarann said.

“I consider myself a child of war. The generation that is around me, my peers,” she said. “We had so much potential to make the country better, too, and it was all shattered.”

Sarann graduated from Simmons College in Boston with a bachelor’s degree in marketing and sociology and later earned a masters in public administration from New York University. She has worked at Radio Free Asia’s Department of Audience Research, Training & Evaluation since 2006.

Family tribute

Maysoury Nuon, mother, died 1982